At the year’s final session of Russian Camp MN, held recently in southwestern Minnesota, the overall peacefulness feels especially precious. Many staffers and campers are concerned about family in Ukraine and Russia. Opposing views of the war between those countries have brought tension among some expatriates.

Yet the camp community has remained intact, as its members negotiate new understandings of what it means to be Russian-speaking Americans and work together to support Ukrainians. Some in the group also struggle at times with identity and their ties to Russian culture.

Why We Wrote This

A Russian language camp in Minnesota that welcomes children through the fall wasn’t sure how it would fare this year because of the war in Ukraine. Organizers found that unity and hope prevailed.

Changes have been made at the camp’s sessions, which are attended by some Ukrainians who have arrived in the United States since the war began. Campers have stopped singing “Katyusha,” an iconic Russian folk song that is closely associated with Russia’s military. Staff members are also making a point of highlighting the regional or religious traditions that have shaped them, since people from more than a dozen nations speak the language.

Seeing young people’s kindness and openness gives those involved hope for the longer term.

“It’s our chance to bring them up as advocates for peace and understanding,” says the camp’s director and founder, Tamara von Schmidt-Pauli. “In the future they can be the people who bring democracy and normalcy back to Russia.”

To look at them running and playing on the campground in the autumn sunshine, they might be any kids enjoying Minnesota’s fall vacation from school. But listening to them, and to the adults cheering them on, reveals something unique about the gathering: Everyone is speaking Russian.

At the year’s final session of “Игра. Unplugged,” or Russian Camp MN, in southwestern Minnesota, the overall peacefulness feels especially precious. Many staffers and campers, some of whom have recently arrived from Ukraine are concerned about family members there and in Russia. Opposing views of the war between those countries have brought tension among some expatriates.

Yet the camp community has remained intact, as its members negotiate new understandings of what it means to be Russian-speaking Americans and work together to support Ukrainians. Some in the group also struggle at times with identity and their ties to Russian culture, but seeing young people’s kindness and openness gives them hope for the longer term.

Why We Wrote This

A Russian language camp in Minnesota that welcomes children through the fall wasn’t sure how it would fare this year because of the war in Ukraine. Organizers found that unity and hope prevailed.

“It’s our chance to bring them up as advocates for peace and understanding,” says the camp’s director and founder, Tamara von Schmidt-Pauli. “In the future they can be the people who bring democracy and normalcy back to Russia.”

“It’s our common language”

Responding to the war has inspired some adjustments here in the woods along the St. Croix River, where campers ages 6 to 18 from across the United States gather to be immersed in Russian without the distraction of their cell phones and tablets. This year families chose from three overnight sessions, including five days in October, and from day camps held in Eden Prairie, Minnesota.

Many in the camp community now talk in more detail about their families’ cultural heritage, discussing the regional or religious traditions that have shaped them. The Russian Empire’s vast conquests and the former Soviet Union’s edict that Russian be the official language throughout its republics mean that people from more than a dozen nations speak the language.

Larissa Rudashevsky, one of the counselors, grew up in Belarus. Her husband is Jewish and from Lithuania. In their family, there’s “not a drop of Russian blood, but it’s our common language,” she explains.

Parent Natasha Taylor of Maple Grove, Minnesota, has sent her youngest son to the camp for the past four years. She is from St. Petersburg but also has Ukrainian heritage; her husband is from Ukraine and has a brother in Kyiv, the country’s capital. Her son, who is 14, is practicing language skills that help him better communicate with Ms. Taylor’s mother, who does not speak English. “We are all so interconnected and intertwined,” she says of Russian and Ukrainian people living in the U.S. While she has seen “cracks in relationships” between people who disagree about the war, she has not observed this happening with the camp.

Besides more discussions around diversity, there have also been other changes, say Ms. Von Schmidt-Pauli and her co-organizers Daria Dzhalalova and Irina Safonov.

“We no longer play Battleship,” Ms. von Schmidt-Pauli says, referring to the popular submarine-themed game. She adds, “Injured, drowned, killed – these words aren’t abstract to kids now.” And they’ve stopped singing “Katyusha,” an iconic Russian folk song that is closely associated with Russia’s military.

The camp’s lodge is also no longer known as the Kremlin, Russia’s symbolic seat of government. But the cabins, all part of a Kiwanis Scout Camp, are still named after cities across the former Soviet Union. And the footpaths are named for thoroughfares in the Russian cities of St. Petersburg and Moscow, and Kyiv in Ukraine.

While the organizers hope the camp offers respite from worrying about the war, meeting peers who have faced it firsthand has given the American campers a more intimate view of its realities. “It’s one thing to hear something on the news,” Ms. von Schmidt-Pauli says. “It’s another thing to sit around the campfire and hear a teammate tell you something.”

Welcoming refugees

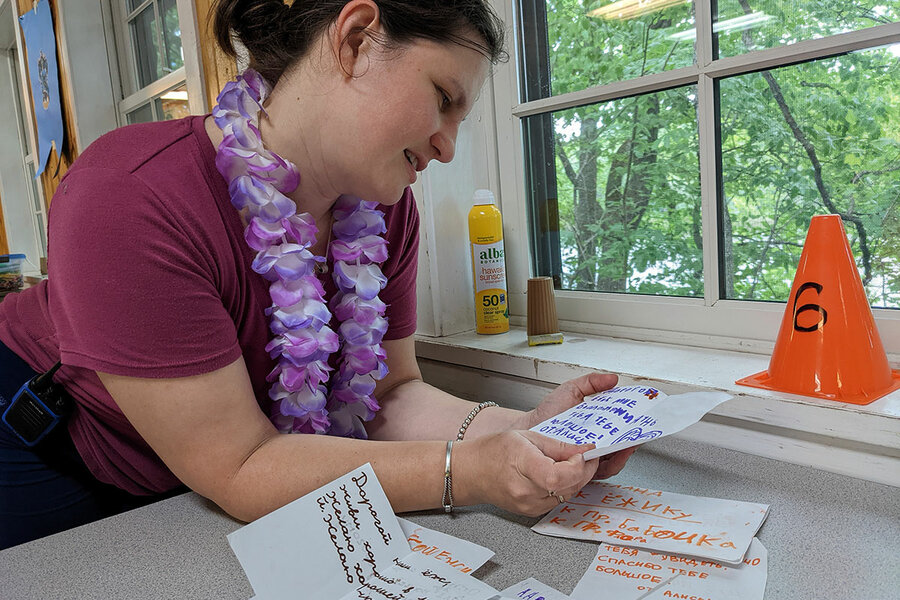

Masha Kryvoruchko, a seventh grader from Ukraine who came to Minnesota in the spring with her mother to escape the war, is a camper at the fall session. When asked through a translator what her favorite activities have been, she smiles and quietly replies, “Everything.” She elaborates that she’s liked playing a live-action version of the popular video game “Among Us”; making pirozhki, a type of bun with sweet or savory fillings; and playing the piano in music class.

Speaking Russian at the camp – and at home with her mother and father, the camp’s music teacher – has allowed 17-year-old Paulina Frayman, now a counselor-in-training, to connect with Ukrainian newcomers who did not speak any English when they started this year at her high school in the Twin Cities area. “They get thrown into the mess of things, and they just have to adapt to everything,” she says. “I got to meet them and help show them that there is someone here that can help them get around the school and that if they need help with anything they can ask.”

Since March, approximately 900 Ukrainians have accessed support services in the state, a spokesperson from the Minnesota Department of Human Services says, noting that others may have arrived but not used services. The camp’s organizers estimate that between 45 and 50 Ukrainian children have attended a day camp or overnight session since June, with some children attending more than once and the camp covering their tuition. About 400 children overall attend the various camp sessions, including the one in the fall.

Though many Ukrainians embraced the Ukrainian language after the USSR dissolved in 1991, most people in the country still speak and understand at least some Russian, and in some areas Russian remains predominant. This year many Russian-speaking Ukrainians have become passionate about learning Ukrainian, says Walter Anastazievsky, interim community outreach manager at the Ukrainian American Community Center in Minneapolis. He encourages that, but he also welcomes all supporters of the country and its people, regardless of what language they speak. “It doesn’t need to be a point of division,” he says.

A common mission

Ms. von Schmidt-Pauli grew up in St. Petersburg and immigrated to the U.S. when she was 20. She loved teaching her American friends about her home country and later sharing its language with her students at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where she is an instructor in Russian Studies, and with her American-born daughters. She launched the sleep-away camp in 2017. When Russia attacked Ukraine, she felt a crisis of identity. She struggled for a time this year, unable to feel proud of Russian language and culture.

She and other camp members have found that their shared opposition to the war and advocacy for its victims bind them together as much as their common language. Despite having concerns, she says that not one family withdrew from any of the 2022 sessions. Instead, supporting Ukraine has brought many of them closer, with families working on fundraisers and gathering clothing and medical supplies to send to Ukrainian soldiers.

Camp organizers are already brainstorming ideas for next year’s sessions. “I am very grateful to the camp community,” Ms. von Schmidt-Pauli says, “who trust us and keep coming and keep staying together as a community without hate.”