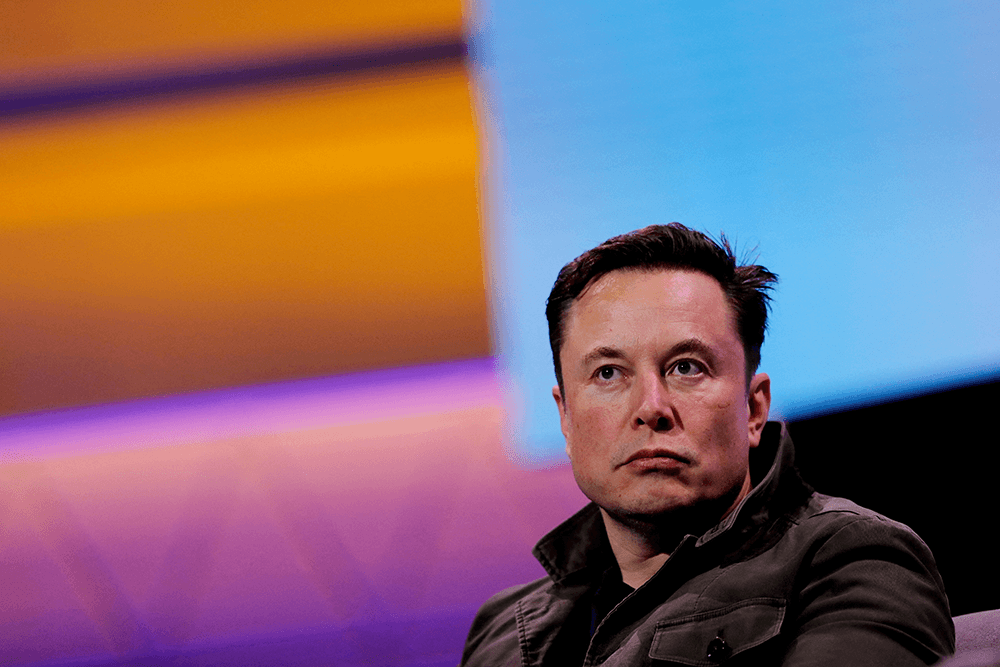

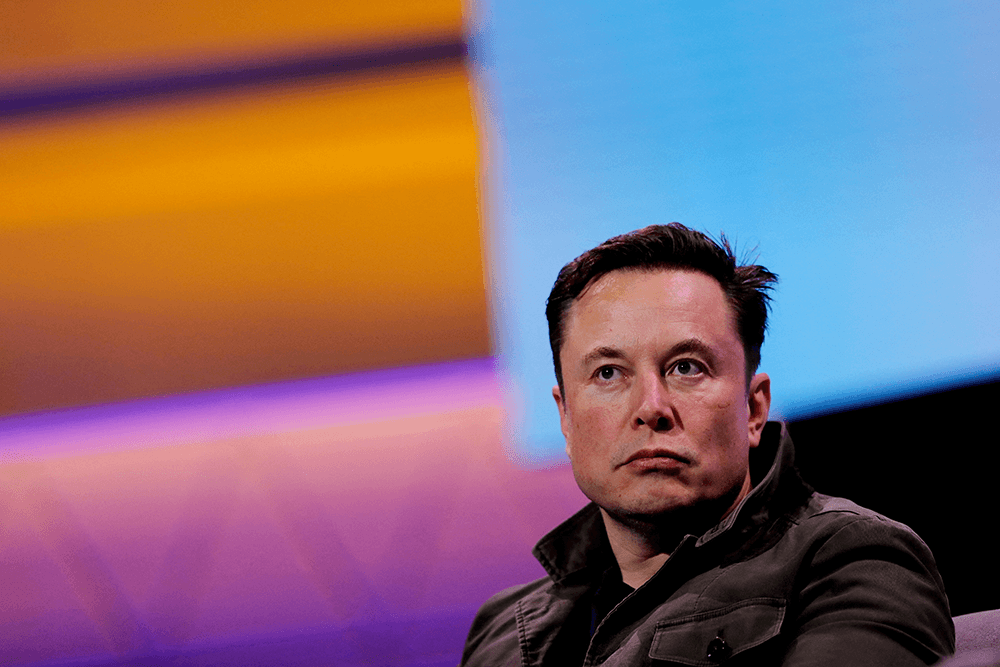

What happened to Twitter under the leadership of billionaire and tech mogul Elon Musk was not surprising to anyone who’s been paying attention.

True, all but the most cynical among us probably thought it’d take longer than a month to chase off millions of dollars in advertiser revenue, reportedly beg staffers he’d fired to come back, and fix problems he’d caused — like accidentally locking users out of their own accounts and turning his $44 billion dollar purchase into the laughingstock of the social media universe. But catastrophe was all but guaranteed the moment Musk signed the dotted line to purchase Twitter and run the company. The bird app never stood a chance.

I will admit that Musk is a man of certain talents. For example, as an executive, he’s good at exploiting the work of others and taking credit for it. He’s a very “creative accountant” and has an undeniable knack for self-promotion. But sarcasm aside, Musk is not a good boss nor is he a social media genius.

What Musk is is rich. The richest man alive! And his unfathomable pools of wealth have done what his limited managerial experience could not: They have convinced people that he is a very smart man. People see the number of zeros at the end of his net worth and figure that he must be good at something. After all, he has a lot of money, and people who have a lot of money must be smart otherwise they would be poor, right? This way of thinking is so fundamental to the U.S. enterprise that we are terrified by the thought of really considering its merits.

You can see this in the strange and complex history of interpreting Jesus’ words about wealth in the gospels. The Lord did not mince words about money. You’ve heard the story of the so-called rich young ruler, who asked Jesus what he had to do to be saved and balked when he was told to sell his possessions. “Truly I tell you, it is hard for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of heaven,” Jesus told his disciples “Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Matthew 19:23-24).

This is seemingly a pretty straightforward story: simple setup, concrete analogy, easy life application. “The Scripture is clear,” as Christians love to say whenever a Bible verse seems particularly obvious. But, in practice, Christian history is littered with otherwise intelligent, faithful people trying to explain why Jesus couldn’t have possibly meant what he said here.

The most famous example might be the theory that Jesus was not referring to an actual camel going through a needle’s eye, but was instead talking about a nearby gate nicknamed “the needle’s eye” which was a little too small for camels unless you removed all their excess baggage. It’s an interesting theory that dates back to at least the fifteenth century and would be a lot more compelling if there was any evidence for the existence of such a gate. But as writer and pastor Vincent Pontius points out, there is no evidence of this gate ever existing.

Interestingly, some scholars have argued that the word “camel” is actually an ancient typo. No less a church father than Cyril of Alexandria noted that the Greek word for “camel” (kamêlos) is very close to the word for “cable” or “anchor rope” (kamilos). Cyril believed Jesus actually said the latter, and Jesus was referring to threading a needle with an absurdly large rope used to anchor boats to the dock. The likes of Italian scholar Manlio Simonetti and Assyrian translator George M. Lamsa agreed with Cyril’s take. This interpretation has a little more rhetorical clarity, so it seems possible — I’ll leave that debate up to smarter people — but it wouldn’t change the passage’s meaning in any significant way.

In any case, the point is there is no earthly reason to avoid taking Jesus’ words in Matthew 19 at absolute face value. He wasn’t referring to some sort of “spiritual” poverty completely disconnected from material wealth. In the story of the rich young ruler, the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, and even the example of his own meager life, it’s clear that Jesus’ relationship with wealth was adversarial. We ignore his exhortations against wealth at our own peril. There are really no two ways about it.

But, where there’s a will there’s a way, and the will to love both God and money is strong. At present, I think most of us have decided that the easiest way to avoid grappling with verses like Luke 6:24’s “woe to you who are rich” and 1 Timothy 6:10’s “the love of money is the root of all evil” is to define “rich” and “love of money” in narrow terms. Under these terms, being “rich” and “loving money” only applies to cartoon supervillains and long-dead royalty. Certainly, we don’t suffer from the love of money. Sure, we want to have it, lots of it, more than we could ever need; and yes, we admire people who make so much of it that we will ignore or excuse their every fault and treat them like aspirational sages. But we don’t love money.

“Perhaps, to avoid trying to serve both God and Mammon, one need only have the right attitude toward riches,” writes biblical scholar and theologian David Bentley Hart, mocking our interpretations. “But if this were all the New Testament had to say on the matter, then one would expect those texts to be balanced out by others affirming the essential benignity of riches honestly procured and well-used. Yet this is precisely what we do not find.”

Jesus’ warnings against wealth were radical from the jump, but they’re particularly revolutionary now, in whatever stage of capitalism this is. Because in the United States, “love of money” is the gas in the engine, the beating heart of the whole shebang. Our entire society is premised on the accepted truth that people do love money, want to be rich, and will devote their lives to making it happen. You start pulling that thread and pretty soon, no sweater.

And I think this is where we must start to adjust our perspective on wealth: We must reject the idea that wealth has any bearing on a person’s true acumen, potential, or value. This is harder than we might think and takes some deliberate work. Frankly, it might be harder and more important to rethink our ideas around poverty, recognizing that a person’s lack of money doesn’t tell you anything about the value of who they are, what they’re capable of, or what they have to offer the world.

If we were to take this seriously, we would have to stop equating the presence of unhoused people with a rise in crime, or soaring profits as a telltale sign of God’s favor. We might have to rethink our career goals, our voting habits, and maybe even the place we live. It sounds scary. It should sound scary. Even the disciples, when they heard Jesus’ words about the needle’s eye, sounded a little panicky. “When the disciples heard this, they were greatly astounded and said, ‘Then who can be saved?’ But Jesus looked at them and said, ‘For mortals it is impossible, but for God all things are possible’” (Matthew 19:25-26).

I doubt we will learn much from this whole Twitter debacle. Musk will be fine. Musk’s $44 billion loss will be seen as a forgivable fluke by the same people who would refuse to give a homeless man a single penny if they saw him buying a beer at a convenience store.

Society will always look to the rich to solve its problems. Whether it’s Musk with Twitter, the wealthy businesspeople running for political office, or our cabal of nightmare corporations we’ve entrusted to fight climate change, we remain erroneously convinced rich people hold the answers to the world’s problems.

We must begin recognizing that the rich are no more special than we are, and wealth is not a blue checkmark of competence or virtue. Not in this world and certainly not in heaven. And if we can do that, then perhaps we can also begin to understand that if God’s community does indeed belong to the poor, as Jesus said, then they might be worthy subjects of our respect in the here and now.