(RNS) — Historians are well aware that debates about the past are inseparable from debates about the present. This year, perhaps like no recent Thanksgiving, Christians in the United States are reckoning with our popular memory of the Pilgrims and the “First Thanksgiving,” and what those founding stories tell us about one of the most divisive current culture-war issues — namely, whether the country was founded as a Christian nation.

There is a logic to this: Thanksgiving is a civil holiday, decreed by the state, not the church, yet we instinctively assign religious significance to it, and we remember it as originating in a specific historical moment in 1620. More than any other American holiday, Thanksgiving contains the strands of national identity, religious heritage and historical memory, all inextricably interwoven.

For those who emphasize America’s Christian roots, then, getting right with the Pilgrims is never only about understanding the origins of a treasured holiday. The Pilgrims’ story becomes “the first chapter in the American story,” and the Pilgrims become honorary founders of a nation — one officially established more than a century and a half after their arrival. This week social media will be awash in reminders that the U.S. “was founded” by devout Christians who came to American shores four centuries ago “in search of religious freedom.”

Prior to the American Revolution, the Pilgrims were rarely remembered outside of Massachusetts. As the newly independent English colonists began to reinterpret their past as “Americans,” however, they went in search of a new origin story, which the Pilgrims answered. By the turn of the century, commemorations of the Pilgrims routinely portrayed them as religiously motivated but earthly minded travelers who self-consciously laid the foundation for a new nation.

ARCHIVE: Where does Thanksgiving come from?

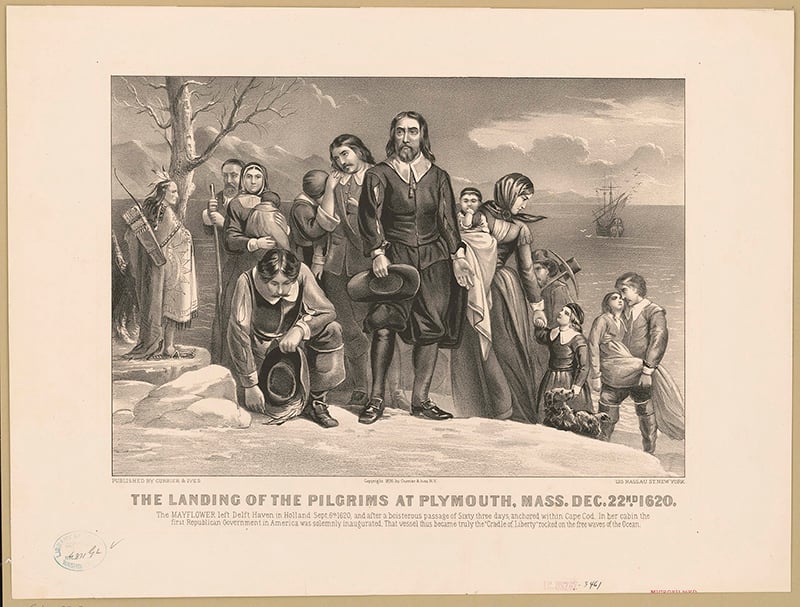

“The Landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, Mass. Dec. 22nd 1620” Image courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

Speaking at the bicentennial of the Pilgrims’ landing in 1820, the silver-tongued Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster figuratively positioned the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock (a landmark no Pilgrim writer ever mentioned) and invited his audience to listen in as their ancestors contemplated the future of the land to which God had brought them.

“We shall here begin a work that shall last for ages,” the senator imagined the Pilgrims saying. “We shall plant here a new society, in the principles of the fullest liberty and the purest religion,” and soon “the temples of the true God shall rise.”

Toward the close of the 19th century, a writer for Ladies’ Home Journal employed the same trope, although this time it was the Pilgrims’ elder William Brewster who stood alone on the rock and prophesied:

Blessed will it be for us, blessed for this land, for this vast continent! Generations to come shall look back to this hour . . . and say: “Here was our beginning as a people. These were our fathers … Their faith is our faith; their hope is our hope; their God our God.”

Politicians, preachers and writers echoed the point: The tiny Pilgrim band had forged the “nucleus of a mighty civilization.” They “were among the main foundation-layers of our Great Republic.” They brought with them “the germ of our national life.”

In this view, still common today, the Pilgrims’ journey ended when they reached the shores of America. The future United States was their Canaan, their Promised Land.

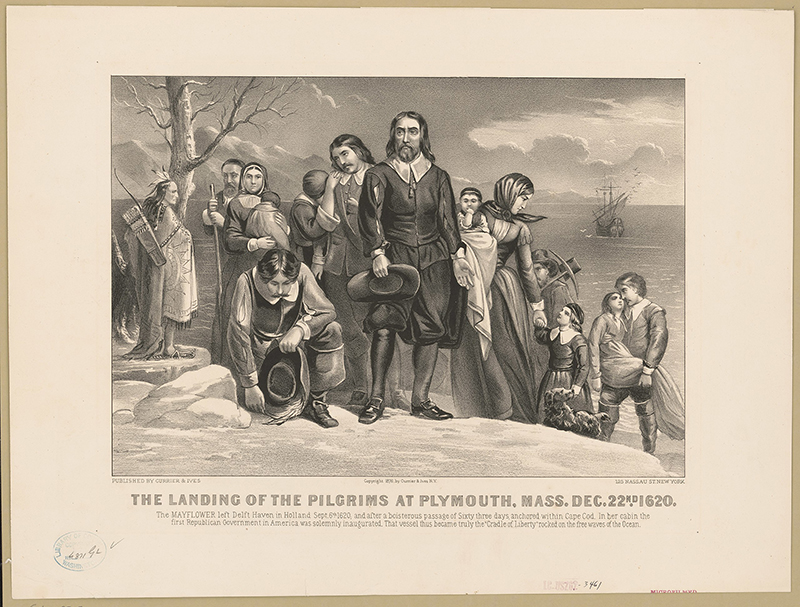

“The First Thanksgiving 1621” by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, circa 1912-1915. Image courtesy of LOC/Wikimedia/Creative Commons

It can be inspiring to remember their story that way, but there is this problem: That’s not how the Pilgrims themselves saw it.

Certainly, the English Christians we call the Pilgrims were searching for an earthly location where they could worship in the manner they believed the Bible commanded. But to the degree that the Pilgrims thought of themselves as “pilgrims,” they meant that they were temporary travelers in a world that was not their home — much less a nation.

This is clear from the context in which William Bradford famously used the term in his history “Of Plymouth Plantation.” The Pilgrims’ governor movingly described the departure from Holland, where they had first moved to escape discrimination in England. With “an abundance of tears,” those in the Leiden congregation who were headed for New England left “that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting place near twelve years; but they knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, but lift up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country, and quieted their spirits.”

As he penned these words, Bradford was almost certainly thinking of the 11th chapter of the Bible’s Book of Hebrews, that great survey of Old Testament heroes of the faith. There, we read that these men and women “confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on earth.” The biblical writer goes on to explain that any “that say such things [i.e., think of themselves as pilgrims], declare plainly, that they seek a country,” but the country sought is a “heavenly” one.

In a much less known passage, the Pilgrim Deacon Robert Cushman employed similar imagery. In an essay published in 1622, Cushman reviewed the argument for “removing out of England into the parts of America.” He emphasized that God no longer gave particular lands to particular peoples, as he once had given Canaan to the nation of Israel. “But now we are all in all places strangers and pilgrims, travelers and sojourners,” Cushman observed, “having no dwelling but in this earthen tabernacle.”

RELATED: What’s on America’s Thanksgiving menu? Start with religious diversity.

Echoing the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Corinthians, the deacon elaborated, “Our dwelling is but a wandering, and our abiding but as a fleeting, and in a word our home is nowhere, but in the heavens, in that house not made with hands, whose maker and builder is God, and to which all ascend that love the coming of our Lord Jesus.”

It is possible for Christians in the United States today to remember the Pilgrims as our spiritual ancestors and still preserve their understanding of “pilgrimage.” But when we remember them as our national ancestors — as key figures in the founding of America — we refashion that sense of pilgrimage into something they would neither recognize nor espouse.

(Tracy McKenzie is professor of history and holds the Arthur Holmes Chair of Faith and Learning at Wheaton College. This essay is adapted from his book “The First Thanksgiving: What the Real Story Tells Us About Loving God and Learning from History.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)