(RNS) — Ruth Bell Graham, the wife of evangelist Billy Graham for more than 60 years until her death in 2007, was revered by white evangelical women of her time. Beautiful and devout, warm and acerbically witty, she established herself as a personality independent of her husband, yet fully on board with the evangelical model of wifely submission.

A new biography of Graham examines this paragon of 20th century white Christian womanhood in all its complications. Anne Blue Wills, a professor of religion and chair of the department of religious studies at North Carolina’s Davidson College, took 10 years to write Graham’s biography, leaning heavily on her published poetry, innumerable articles in print and appearances on TV. She also interviewed two of Graham’s five children (Gigi and Bunny); Franklin Graham, Anne Graham Lotz and Ned Graham declined to talk to her.

Wills did not have access to Graham’s letters and journals, which had previously been shared with Patricia Cornwell, a family friend, for her 1997 biography “Ruth, A Portrait.” Yet Wills has been able to draw a rich portrait.

“An Odd Cross to Bear: A Biography of Ruth Bell Graham” by Anne Blue Wills. Courtesy image

Ruth Graham was born in 1920 to missionary parents serving at a hospital in Tsing Kiang Pu, China, (now Huaiyn) and educated at Wheaton College, outside Chicago. Graham’s parents, Dr. Nelson and Virginia Bell, both Southerners, were deeply devoted and uncompromising Presbyterian missionaries. Ruth, their second daughter, admired them and wanted nothing more than to model her life after theirs. She changed her mind when she met Billy Graham at Wheaton, and eventually agreed to a sacrificial Christian life in service to his larger mission as an evangelist.

At her insistence, Ruth and Billy settled in Montreat, North Carolina, a tiny mountain town near Asheville, where her parents had retired. Almost single-handedly, she designed and built a mountain home and reared five children while Billy (whom Ruth always called Bill) led hundreds of crusades around the world, becoming easily the most recognizable American evangelist of the 20th century.

Unlike the Catholic Phyllis Schlafly or the Protestant Anita Bryant, Graham did not publicly campaign against the second wave of feminism, which began in the 1960s. But like them, she opposed the women’s rights movements even as she benefited from some of its gains by slowly becoming a public figure as an author and a speaker.

Religion News Service spoke to Wills about her book, “An Odd Cross to Bear: A Biography of Ruth Bell Graham.” The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

What drew you to Ruth Bell Graham?

It wasn’t my idea. My professor Grant Wacker asked me to write a paper about Billy Graham from a gender perspective for a conference. I wrote that Ruth helped to strengthen (Billy’s) manly image by being ultrafeminine and ultracapable as a woman. Several people in the audience said, “You should write a book on her.”

Anne Blue Wills. Courtesy photo

Also, as a child my family often went to Montreat. My aunt’s house was right down the street from where Ruth’s parents lived and where she first bought a house. So I feel like I have a connection to her. She was also in the same generation as my mother. Trying to understand that generation of white Protestant women — that had an allure for me.

It must have been hard to write this book without access to Graham’s personal letters. How’d you do it?

I worked for a year or more to get access to them and to reassure people that I’m an academic. But it didn’t go anywhere. When Patricia Cornwell’s book came out, it didn’t sit well with some people in the family. She and Ruth didn’t speak for years after it came out. What I did instead was try to find as many accounts of Ruth — things she wrote about herself and things people wrote about her. She figures in a lot of memoirs and there’s useful press coverage. And then I used her poems and tried to make it work that way and set her in the context of what was going on with white evangelical women during that time.

Historian David Hollinger writes about the “cosmopolitan missionary,” who became much more ecumenical, tolerant and inclusive of Indigenous peoples as a result of his travels. That was not Ruth Graham’s parents’ experience, right?

Ruth Graham shows her husband, evangelist Billy Graham, the house in Huaiyin, China, where she was raised until she turned 17. They visited the site in 1988. RNS file photo

That’s right. In fact, the (1912) Hocking Report said Protestant missionaries in China should be focused more on social service than on conversion. Nelson had a very negative reaction to that. Virginia and Nelson felt very strongly that missions were about soul work. They worked in a hospital and provided cutting-edge care to a very isolated part of China, but they were there because they could share the gospel with people they were treating. He was very allergic to the idea that missions should aim to transform social conditions. They were wholeheartedly into the distinctiveness of American Christian missionaries and the witness they brought.

Did Ruth have much contact with Chinese children? Did she speak Mandarin?

Her parents saw the Chinese, who were not Christian, as subhuman. There were some children of their household help they had contact with. But the goal for the (Bell) children was to keep them as American as they could and to expose them to sacrificial dedication of the Christian work. They made sure the children’s education, their clothing, the things they ate, the books they read, the games they played, were of American extraction. Nelson and Virginia spoke Chinese and probably Mandarin. I don’t know if Ruth did.

At Wheaton, Ruth had a crisis of faith. Was it your impression that once she got over it she never looked back?

Yes. She’s around a bunch of new people in a new context. She’s half a world away from the place she considered her home. She feels isolated and distanced from God, who she always felt very close to. She was also taking classes that challenged her to think through some of the commitments she made. That can be disorienting. But her sister Rosa, who was also at Wheaton, and her boyfriends and a professor helped her get through it. In crisis moments she did not doubt God’s presence. She tried to get close to God by being alone, studying Scripture and trying to listen to what she felt God was trying to say to her.

Ruth Graham at her home in Montreat, North Carolina, in an undated photo. Photo courtesy of Billy Graham Evangelistic Association

As a girl, Ruth wore blackface for Halloween. Late in life she quoted from white supremacist Thomas Dixon (author of “The Clansman,” later adapted into the movie “Birth of a Nation.”) She was silent on the civil rights movement. What were her views on race?

She refused to acknowledge the civil rights movement, except to react against the (civil rights) protests and rioting, which she found distasteful because it was a disrespectful way to behave, not because it was a Black revolution. That gave permission for women who admired her to also disengage from that. She and Billy had Muhammad Ali over at their house. And Billy made efforts to diversify the podium at his crusades. But Ruth didn’t have to do that. Their housekeeper for several decades was Beatrice Long, an African American. Ruth talked about “Bee Long, our negro housekeeper.” That showed she was speaking the language of her moment. She was of her generation in terms of race and white privilege and had a genteel white supremacy that a lot of us still benefit from.

Ruth had a high view of law enforcement and believed they were to be treated with the utmost respect. Was it born out of her faith?

It was spooky to be writing about this when George Floyd was killed and thinking about her comments about the death penalty. She said she always felt safer when she went to a country where the death penalty was legal. She very clearly valued the work of law enforcement. She was solicitous and apologetic when they came to her house with Franklin in tow during his rebellious stage. She had a law-and-order view of the world. It went back to this notion of respect for authority. Children should respect their parents. Citizens should respect their governmental leaders. People should respect police officers, who are trustworthy and sacrificial.

Ruth talked about the need for young brides to “adjust” to their circumstances. Do you think she made peace with her role as a helpmeet to her husband, or was there a part of her that wanted a bigger role?

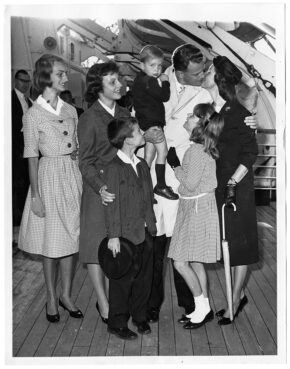

Evangelist Billy Graham greets his wife and family in New York upon their arrival on the Queen Elizabeth ship in 1960. Ruth Graham and the children spent the summer in Switzerland. Billy Graham holds his son, Ned, 2. The other children are, from left, Anne, 12, Gigi, 15, Franklin, 8, and Bunny, 9. RNS archive photo. Photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society

I think the way she reconciled herself to a supporting role was by thinking of it as sacrificial. This was a worthy thing to submit to. But she did exercise a lot of authority over (Billy) by making sure he stayed in the path of an evangelist. If he was tempted to be a pastor or a political figure, that was not what she signed on for. She had committed to help him in the work of evangelism. Part of the sacrifice for her was the mental toll of being the main parent. She loved it and gave herself to it very energetically. At the same time, she had Bibles all around the house. There was always this divided attention to the children and her concern with developing her own faith and perspective on what God was communicating to her.

Your book is titled “An Odd Cross to Bear.” Where does that come from?

That’s from Cornwell’s book. People asked Ruth, “What’s it like to be married to Billy Graham?” Apparently at one point she said, “It’s an odd cross to bear.” He became one of the most important religious leaders in U.S history and that’s where the oddness comes in. It was a triumph. They accomplished what they set out to do. It was an amazing success. But she gave up a lot. To be able to live with that, that’s an odd combination — to be successful and also really sad in the midst of that. That starts to get at what she communicated about that.

RELATED: From shoeboxes to war zones: How Samaritan’s Purse became a $1 billion humanitarian aid powerhouse