Back in November, I wrote about the discovery of an ancient lice comb that was engraved with the oldest known sentence written in a very early version of the proto-Canaanite alphabet.

The comb, found in the southern city of Lachish, was dated to around 1700 BCE. What remained of the crudely scratched letters were translated to mean, “May this tusk root out the lice of the hai[r and the] beard.”

The comb now has competition for the “Most Exciting Ancient Language Discovery of the Year” award.

In the most recent issue of Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archaéologie Orientale, Andrew George and Manfred Krebernik reveal the discovery of two Old Babylonian tablets from around 1800 BCE that contain a surprising bilingual text.

A more accessible review of the article, including a photo of the tablets, is available in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz.

The tablets first came to light during the Gulf War, when many antiquities were endangered, both by explosives associated with the fighting and by sabotage from extremists seeking to rid Iraq of relics or texts pointing to its pagan past.

They were among thousands of artifacts taken out of the country to an overseas location. Some say that they were removed for safekeeping, while others contend that they were stolen. My hope, as things continue to stabilize in Iraq, is that they will be returned.

The tablets languished in storage for 30 years before George and Krebernik recognized that the texts, divided into two columns, contain a series of words and phrases from an old Amorite language in one column with their translation into Old Babylonian in the other.

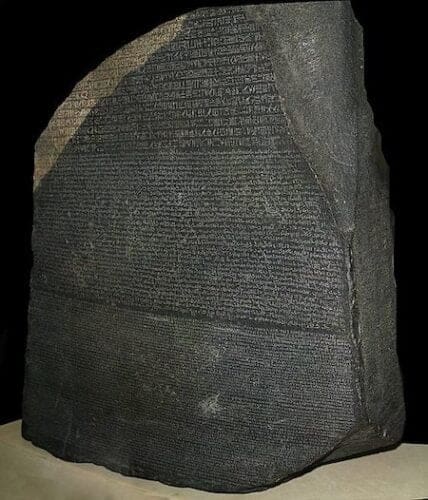

The Rosetta Stone. (Credit: Hans Hillewaert / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 / https://tinyurl.com/25zjxr6t)

The find doesn’t rank up there with the Rosetta Stone’s trilingual text (Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs) that helped linguists decipher the ubiquitous hieroglyphic inscriptions that adorned Egyptian monuments and tombs.

Nor can it match the monumental Behistun inscription, which Darius the Great had carved on a cliff face to tout his achievements in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. That trilingual treasure enabled scholars to begin untangling the exceedingly complex cuneiform language used by the Babylonians and Assyrians.

But the newly interpreted texts have their own significance because they are an early attestation of the Northwest Semitic languages that came to include Canaanite, Hebrew, Moabite, and other dialects spoken in Palestine.

Many Bible readers are unaware that the Hebrews would have had little difficulty communicating with the people groups they sought to displace and continued to live among: most of them spoke versions of Northwest Semitic.

Scholars have long known that such a language had developed by the Middle Bronze Age, and usually associated it with the emergence of a nomadic people group west of the Euphrates known to the Sumerians as Mar.tu, the Babylonians as Amurru, and the Assyrians as Amor. The English term “Amorite” was coined for both the people and the language.

Prior to the recent discovery, inscriptional evidence of the “mother language” for Northwest Semitic was limited largely to proper names embedded in tablets inscribed by a dialect of Akkadian that the Amorites adopted for writing.

On the tablets under discussion, however, George and Krebernik discovered a trove of commonly used words and phrases spelled phonetically with cuneiform characters in the left-hand column, with their translation into Old Babylonian on the right.

They realized that many of the everyday Amorite words, phrases, and grammatical constructions were remarkably similar to their Hebrew descendants.

Scholars didn’t need these bilingual texts to translate either Babylonian or Hebrew, but they offer an important window into the development of Northwest Semitic. They demonstrate, among other things, that in the days of Hammurabi there were many people who spoke a language much like what emerged as the Hebrew we know from the Bible.

I suspect many readers will be yawning by now, if they made it this far, but stick with me: consider that the purpose of the bilingual tablets was to take the words of a rather obscure tongue and translate their meaning to readers of another language.

Might we profit from imagining ourselves as living tablets, taking little-understood (or misunderstood) biblical teachings and living them out in a way that demonstrates their true intent?

When scripture is twisted to support antisemitism, white supremacy, or Christian nationalism, isn’t it important for Jesus-followers to flesh out the real meaning of love and justice in the way we live?

Now that would be a real discovery.

Professor of Old Testament at Campbell University Divinity School in Buies Creek, North Carolina, and the Contributing Editor and Curriculum Writer at Good Faith Media.