Patrick Bringley didn’t set out to work as a guard at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. With a plum post-college job at The New Yorker, he was on an ambitious career track when his older brother, Tom, was diagnosed with cancer.

When Tom died in 2008 at age 26, Bringley, devastated, felt compelled to take a breath, to “drop out of the forward-marching world and spend all day tarrying in an entirely beautiful one.”

Why We Wrote This

Art has the power to move people out of grief and stagnation. For one author, looking closely and cultivating curiosity brought him to a place of renewal and gratitude.

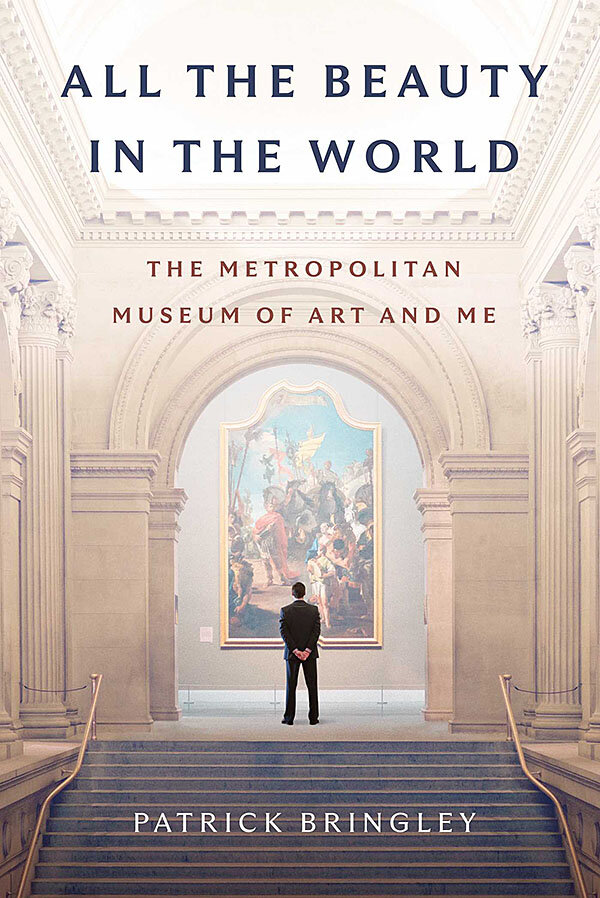

As he explores in “All the Beauty in the World,” Bringley finds the Met an extraordinary place in which to grieve, and he is eloquent, if at times wide-eyed, in expressing the ways that art assists him in that process.

He approaches the museum’s vast collection of roughly two million objects with openness and wonder. He is equally curious about its hundreds of guards, who assist and keep eyes on millions of visitors each year. Bringley describes the boredom and discomfort that accompanies the job, as well as the guards’ inside jokes and chatty camaraderie.

Ultimately, “All the Beauty in the World” is about how to look at and appreciate art, a practice Bringley has devoted himself to with earnestness and humility.

Patrick Bringley spent a decade as a guard at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, but don’t expect any scandalous behind-the-scenes revelations in his appealing and tender memoir, “All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me.” Instead, the author chronicles his personal transformation amid a magnificent collection of galleries watched over by a diverse and genial workforce.

Bringley hadn’t set out to work at the Met. With a plum post-college job at The New Yorker, he was on an ambitious career track when his older brother, Tom, was diagnosed with cancer. When Tom died in 2008 at age 26, Bringley, devastated, felt compelled to take a breath, to “drop out of the forward-marching world and spend all day tarrying in an entirely beautiful one.”

The book captures Tom’s intelligence and playful personality and conveys the magnitude of the author’s loss. Bringley finds the Met an extraordinary place in which to grieve, and he is eloquent, if at times wide-eyed, in expressing the ways that art assists him in that process.

Why We Wrote This

Art has the power to move people out of grief and stagnation. For one author, looking closely and cultivating curiosity brought him to a place of renewal and gratitude.

Bringley’s story overflows with wonder, beauty, and the persistence of hope, as he finds not just solace but meaning and inspiration in the masterpieces that surround him.

Perhaps not surprisingly, portrayals of Christ’s crucifixion particularly resonate with the author – and the Met, which was founded in 1870, has plenty of them. Gazing at one, a tempera painting by Fra Angelico, an Italian artist of the early Renaissance, Bringley observes art’s capacity to remind us “that we’re mortal, that we suffer, that bravery in suffering is beautiful, that loss inspires love and lamentation.”

Bringley approaches the museum’s vast collection of roughly two million objects with a similar openness and wonder. (An appendix lists the many pieces cited within the book’s pages.) He is equally curious about its pool of guards, at that time about 400 strong, who assist and keep eyes on an astonishing number of visitors, topping 7 million people in some years. “The glory of so-called unskilled jobs is that people with a fantastic range of skills and backgrounds work them,” he notes, adding that his colleagues are “not only diverse demographically – almost half of the guard corps is foreign born – but diverse along every axis.” The author depicts that heterogeneity in a charming scene: He explains that the Met guards produce an occasional journal of art, poetry, and prose, and he fondly describes its raucous release party, which doubles as an open-mic night, running an eclectic gamut of performances and genres.

Comfortably settled in his museum routine, Bringley is certain that he’ll remain at the Met forever. Training a new guard, Joseph, a middle-aged man from Ghana who becomes a close friend, he gushes about the job. “It would be an indecency, a stupidity, even a betrayal to find fault with such peaceable, honest work,” he writes.

But a lot changes in 10 years. His grief becomes less acute, as grief tends to with time. What’s more, during his tenure at the museum, Bringley marries and becomes a father to two children; his new family further draws him out of his stillness and his sadness. “I no longer need so pristine a setting,” he realizes. “I don’t have to stand on the sidelines, a quiet watchman. I find myself watching parents and children in the galleries and plotting about all that I could do to introduce my kids to the big city and wide world.”

By the time Bringley decides to move on from the Met, we’ve learned a lot about a job that is at once remarkable and unremarkable: the boredom (“Nothing to do and all day to do it,” the guards quip); the discomfort (with shifts of 8 to 12 hours, galleries with wood floors are easier on the feet than those with marble); the inside jokes (it’s apparently not uncommon for visitors to ask where to find the Mona Lisa, which resides not in New York but in Paris, at the Louvre).

“All the Beauty in the World” also offers lessons, drawn from Bringley’s own years of experience, in how to look at and appreciate art, a practice he has devoted himself to with earnestness and humility. After reading this memoir, visitors to the Met or any other museum will likely pay closer attention – not only to the art but to the people watching over it.