NEW DELHI (RNS) — On Jan. 26, when 56-year-old Buddhist engineer-innovator Sonam Wangchuk started his hunger strike in the remote Himalayan desert of Ladakh, Muslims and Buddhists — communities divided for more than six decades — rallied around him.

Wangchuk was on a five-day symbolic fast to draw the attention of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party government to the demands of the people of Ladakh. Currently governed by India, the union territory of Ladakh in the larger Kashmir region has been a major point of dispute among India, Pakistan and China since 1947.

“I didn’t think I’d ever say this, but I am saying we were better off with Jammu and Kashmir than today’s union territory,” Wangchuk said in one of his video statements during the protest.

In 2019, when India’s government, led by Narendra Modi, revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and divided it into two federally governed territories — Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir and Buddhist-dominant Ladakh — Buddhists cheered the decision.

But four years later, the people of Ladakh, who were once friendly allies of the Modi government, have united with the Muslims of Ladakh’s second largest district, Kargil, to challenge BJP’s politics.

Buddhists and Shiite Muslims — the two dominant communities in Ladakh — are now demanding full statehood, greater parliamentary representation, constitutional safeguards and job reservations.

“We were happy back then,” said Lama Nyantak, who has been at the forefront of the protests over the last three years. “But when our utopia ended, all religious leaders decided to come together.”

Scattered protests started right after the revocation in 2019. But Wangchuk’s leadership has broadened the protests, bringing different communities together.

Nyantak explains that Ladakhis initially welcomed the government’s decision to strip Kashmir of its autonomy since they felt sidelined by the Jammu and Kashmir government. They thought the move would safeguard their lands and livelihoods. But now they feel their dispossession has increased.

Ladakh has neither received tribal area status nor has its demand for its own legislature been met. Instead, Ladakhis say the government is pushing ahead with mega development projects that would displace the Indigenous people and threaten their ecologically fragile region.

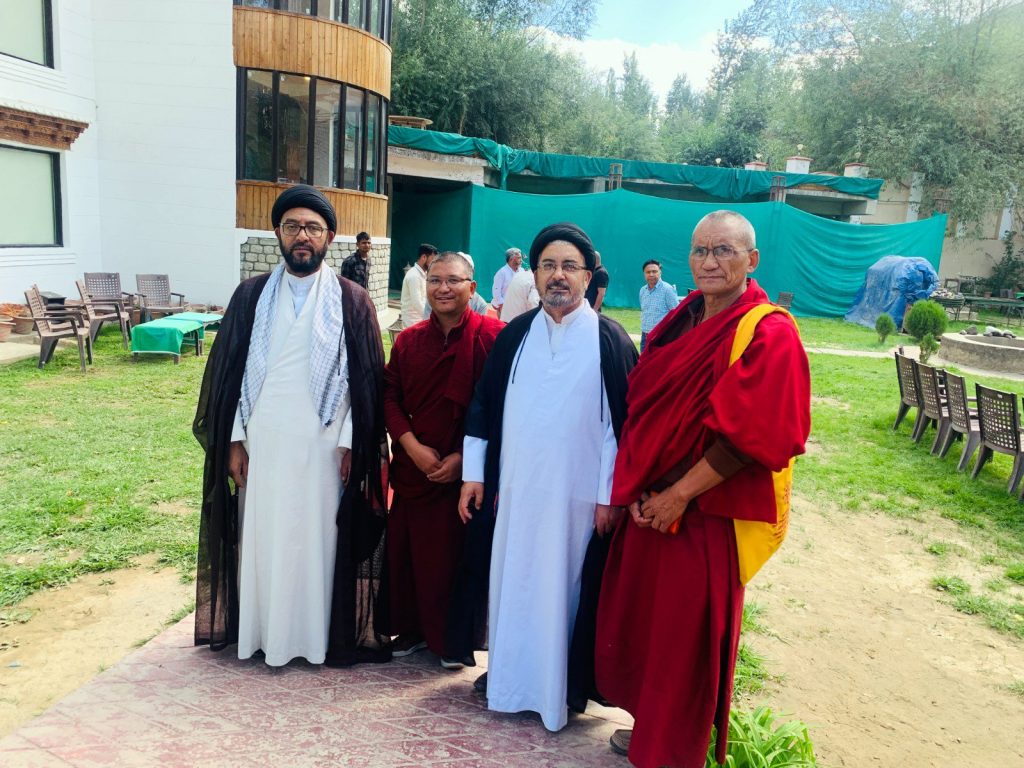

Shiite clerics and Buddhist monks work together to raise their demands for Ladakh union territory in Kargil district, India, in June 2022. Photo by Sajjad Hussain Kargili

“Our protest isn’t just political,” said Sajjad Kargili, a social activist from Ladakh’s Muslim-majority Kargil region. “It is for safeguarding our lands, culture, local languages and environment.”

Kargili believes Ladakh’s change of status has united everyone on the grounds of their shared history.

“We are going from village to village to educate people about our common heritage,” said Dechen Chamgha, a former pastor and president of the Christian Association of Leh district. “During COVID-19 our work suffered, but now religious functions have become major mobilization platforms.”

Chamgha said he narrates stories from the past to forge unity among people and break stereotypes.

“I tell them how Muslims and non-Muslims would cook meat in the same vessel, about interfaith marriages and our vibrant secular democratic polity.”

Spearheading these solidarity-building campaigns in the towns and villages are Leh Apex Body and Kargil Democratic Alliance — civil society groups consisting of social, political and religious leaders.

Feroz Khan, a leading member of the Kargil Democratic Alliance, said the movement has been effective because “faith leaders are trusted more than political parties” in their religious society.

Muslim scholars trained in Islamic law are teaching Ladakhis about the need to preserve their environment and cultural heritage during Friday prayers, gatherings and religious programs.

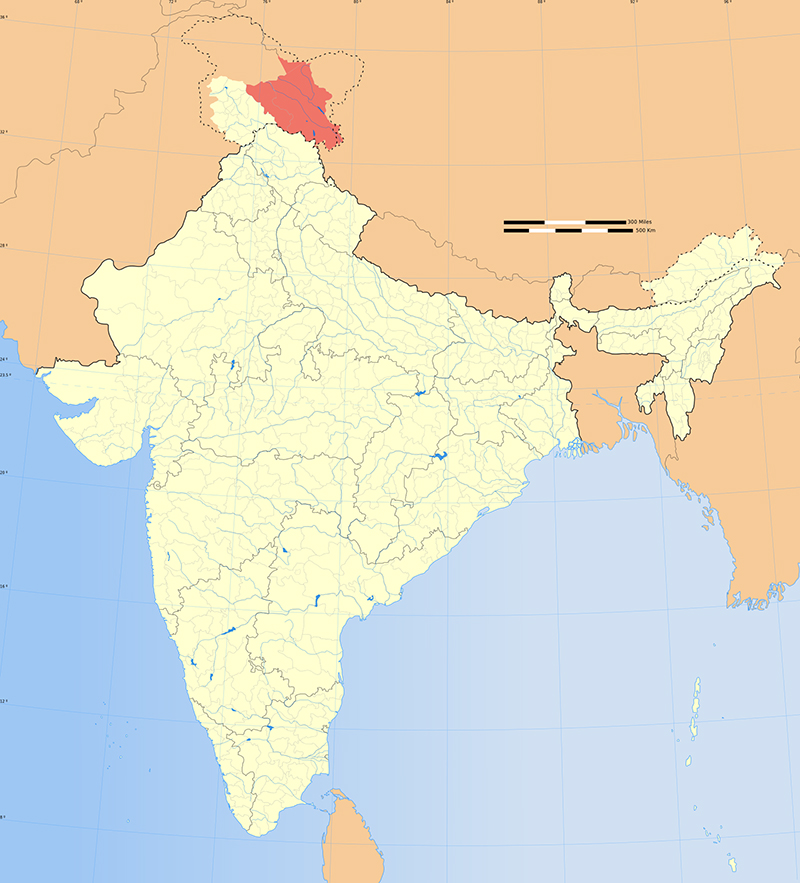

The Ladakh region in norhtern India. Map courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Of particular concern is the government’s green light to several mega development and industrial projects since the region came under its direct rule that locals believe would adversely impact their land.

Seven hydropower projects are proposed to be built on the River Indus, while the government has announced plans for a major solar energy plant in the fragile Pang region of Changthang.

“We are not against development,” said Jigmat Paljor, a social activist and member of the Leh Apex Body. “But these projects should not be at the cost of livestock and the livelihoods of nomadic people.”

Paljor fears that renewable energy projects will be a drain on natural resources such as glacier water and will alter the ways in which land is used in the region, including concerns over the disposal of solar panel debris.

Ladakhi protest groups have said the development projects sanctioned in Delhi would only jeopardize the demography of the region — 97% of Ladakh is tribal — and drown out the voices of Indigenous people.

“These grassroots-level concerns are being raised by our community and faith leaders,” said Nazir Mehdi, the president of Jamiat-ul-Ulama Isna Asharia, Ladakh’s largest Islamic organization.

Mehdi said religious leaders are harnessing the community spirit in the region through their village walks, programs and conferences, as well as social media.

Such online mobilization campaigns proved effective during Wangchuk’s five-day symbolic fast for Ladakhis’ rights.

When Wangchuk held his fast, performed in the open when temperatures dropped to -13 Fahrenheit, Buddhists across Ladakh’s towns and villages organized symbolic retreats to express their solidarity and nonviolent resistance to discrimination.

Social reformist Sonam Wangchuk during his five-day climate fast to “save Ladakh.” Photo via Twitter/Sonam Wangchuk

“On the last day of his fast, Buddhist monks led prayers at the Chokhang Vihara Temple where over 500 devotees had congregated,” said Chering Dorjay Lakrook, the vice president of the Ladakh Buddhist Association. “All the Buddhist monks were supporting Wangchuk’s protest.”

Mohammad Taha, a member of Jamiat-ul-Ulama Isna Asharia, says Ladakh’s diverse Muslim community also turned up in large numbers to support Wangchuk.

“Muslims and Buddhists were kept apart by politicians for their own selfish agendas,” said Taha at the protest site. “Our idea is to strengthen community bonds so Ladakh is saved.”

Even though communal conflicts have not been reported widely from the region, some incidents have created rifts. Last June, for instance, a campaign by a Buddhist monk to lay the foundation of a Buddhist monastery in a Muslim neighborhood of Kargil sparked tension between the two communities. But some Buddhist leaders suspect the monk was manipulated by the BJP government.

Interfaith marriages and accusations of love jihad have also set communities apart in recent times.

But Ladakh’s current interfaith solidarity received a boost last September when Kargil’s leaders handed over a contentious tract of land to Buddhists for the construction of a small monastery.

“The monastery’s construction was a major bone of contention between the two communities since 1969,” said Sheikh Bashir Shakir of the Imam Khomeini Memorial Trust, a socio-religious organization in Kargil. “This step has helped promote communal harmony in our region.”

Religious leaders are talking about initiating more interfaith dialogues around the growing politicization of religious identity and majoritarian politics across India.

“Ladakh’s interfaith traditions embedded in our Indigenous society are a major reference point,” said Dr Qayum of the minority Sunni community. “Those need to be safeguarded against internal threats and the deeply volatile situation along the border with China.”

In February, Ladakh’s political and religious leaders held a major demonstration in the center of India’s capital, New Delhi, to assert their demands. But the government’s response was lukewarm.

“The delaying tactics of the government has emboldened us,” said Shakir. “Our humanism and inclusive approach will hopefully inspire other nonviolent struggles across the world.”