Twelve years ago, thousands of residents evacuated the Japanese port city of Iwaki as the Fukushima Daiichi power station spewed radioactive material over farmlands, rice paddies, and homes.

When yoga instructor Suzuki Kaori returned, her main concern was whether it was safe to raise her children amid the fallout. Reliable data was scarce – the plant operator and government were downplaying the disaster, and some public officials chastised worried mothers for acting “hysterical.” So she teamed up with other women to launch the Mothers’ Radiation Lab Fukushima. They had no formal scientific training, but they were determined to monitor radiation levels and “make the invisible threat visible,” says Ms. Suzuki.

Why We Wrote This

In Fukushima, Japan, a group of concerned mothers show how engaging the public, rather than dismissing its fears, can foster a sense of trust and safety.

The lab’s staff has since grown from two to 15, and they recently acquired two new state-of-the-art machines to help measure beta radiation in everything from homegrown produce to playground soil. The work has renewed importance as Japan plans to discharge radiation-tainted water into the sea later this year.

It’s one of many grassroots efforts helping restore trust following the nuclear disaster, says Shimizu Nanako, professor at the School of International Studies at Utsunomiya University.

“In many cases, it was women that spearheaded those activities to protect children,” she says.

With its gigantic fish market, glass-walled aquarium, and gleaming shopping mall, the Japanese port city of Iwaki bears few visible scars of the massive tsunami that ripped through the area 12 years ago this week.

Yet the threat of radiation from the resulting nuclear meltdown still lingers.

Thousands of residents evacuated Iwaki in 2011 as the Fukushima Daiichi power station spewed radioactive material over farmlands, rice paddies, and homes. When yoga instructor Suzuki Kaori and other parents returned, their main concern was whether it was safe to raise their children amid the fallout. Reliable data was scarce – the plant operator and government were downplaying the disaster, and some public officials chastised concerned mothers for acting “hysterical” – so in November that same year, Ms. Suzuki teamed up with other women to launch the Mothers’ Radiation Lab Fukushima. They had no formal scientific training, but were determined to monitor radiation levels and “make the invisible threat visible,” says Ms. Suzuki.

Why We Wrote This

In Fukushima, Japan, a group of concerned mothers show how engaging the public, rather than dismissing its fears, can foster a sense of trust and safety.

The lab’s staff has since grown from two members to 15, and their work has renewed importance as residents brace for Japan’s controversial plan to discharge radiation-tainted water into the sea after treatment later this year.

It’s one of many grassroots efforts to restore trust following the Fukushima nuclear disaster, says Shimizu Nanako, professor at the School of International Studies at Utsunomiya University, adding that these mothers and other civil society groups have played a “valuable” role in advocating for community welfare.

“Besides nonprofits, much smaller community groups were also created to conduct study meetings about radiation and check radiation levels on routes to schools,” she says. “In many cases, it was women that spearheaded those activities to protect children.”

Power of data

The Fukushima prefectural government measures soil radioactivity in very limited areas near the plant – areas that don’t include Iwaki.

“At the beginning, we were doing the work just to protect the lives of our families,” recalls the lab director, but now they have their sights equally set on the distant future, hoping to leave future generations a fuller picture of the disaster. This requires the help of citizen scientists.

The lab – which is also called Tarachine, meaning “mother” – receives around 2,000 samples each year from the community, ranging from homegrown turnips to vacuum dust. They also measure soil and water radiation, publishing all their findings online.

In some cases, the mothers’ data assuages fear by revealing lower radiation levels than initially assumed. Other times, readings can trigger direct, immediate change. When they detect high levels of radiation in playgrounds, for example, the mothers contact local officials to send decontamination workers who remove the topsoil of the affected areas until radiation readings fall sharply.

In addition to gathering data that has been cited by academic journals, the group operates a clinic and has performed more than 15,000 thyroid cancer screenings throughout Fukushima and in neighboring prefectures. They also run a camp program designed to give kids a break from Fukushima and educate families about radiation safety.

That was Tanaka Noriko’s first introduction to the lab.

“I knew nothing about radiation before the nuclear disaster,” says Ms. Tanaka, who discovered that she was pregnant shortly before the nuclear reactors exploded. Like many other residents, she tried to avoid radiation by swapping local fish and produce – once a point of pride for the Iwaki community – for water and food imported from outside the prefecture.

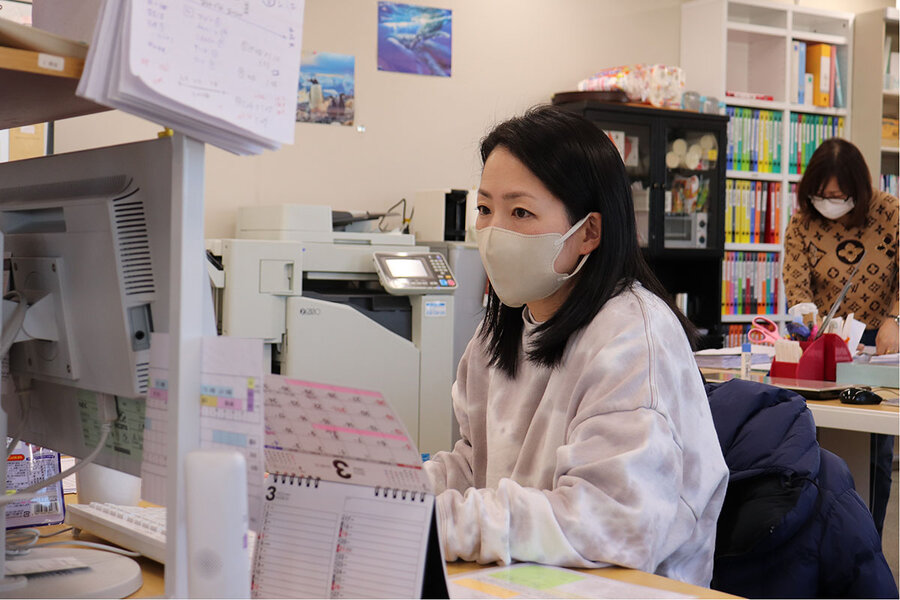

Ms. Tanaka and her toddler eventually joined one of Tarachine’s earliest camp cohorts, and five years ago she decided to join the lab’s staff.

Having access to robust radiation data has allowed her to make informed decisions about her family’s safety, including that of her two primary school children.

“My children receive thyroid screening and take a urine test every year,” she says. “I won’t take them to parks where radioactivity is detected. We avoid mossy areas and side ditches where levels of radiation are likely higher.”

World-class research

To provide trustworthy data, the mothers regularly seek advice from experts like researcher Imanaka Tetsuji from the Institute for Integrated Radiation and Nuclear Science at Kyoto University, and Amano Hikaru, who used to work at the Japan Chemical Analysis Center and the Japan Atomic Energy Agency.

The lab hired Mr. Amano as a technical manager in 2015 when expanding radiation readings to include strontium-90 and tritium.

Tarachine mainly measures cesium-134 and cesium-137, which produce gamma rays, whereas strontium-90 and tritium emit beta rays. Measuring beta rays requires a different laboratory setting, as well as unique instruments and sample preparation, and some argued the work was “too dangerous for women,” Ms. Suzuki recalls. Medical researchers have linked strontium-90, which has a half-life of 28.8 years, to bone cancer and leukemia.

“One of my missions was to enable the mothers to measure beta rays safely,” says Mr. Amano. “The mothers were highly motivated to undertake the task. I was also impressed by their ability and meticulousness.”

Ms. Tanaka, who is in charge of measuring beta rays at the lab, says she understands and is undeterred by the risks.

“Somebody has to do this,” says the former pâtissier, adding that she wears safety goggles and thick gloves when she takes readings.

However, Ms. Shimizu says their work goes largely unrecognized in Japan, where civic activities are held in low regard, especially women-led initiatives. The country ranked 116th out of 146 countries in the 2022 Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum.

Still, Ms. Suzuki says the group’s success is a testament to the trust they’ve developed with local communities and to some degree across the country.

The lab does not receive – nor want – government subsidies, and it is instead funded mostly by donations from Japanese people throughout the country and overseas. Thanks to their support, the group recently acquired two state-of-the-art beta-reading machines costing $343,000 total. Mr. Amano says the mothers are, in effect, running a “world-class” lab.

“Donors understand our independent stance, and they want the money to be spent on children,” says Ms. Suzuki.