(RNS) — Boston University religion professor Stephen Prothero doesn’t believe in fate. Or in divine providence.

But about a decade ago, the universe tapped him on the shoulder and gave him a job to do.

Prothero, who lives on Cape Cod, was at a Labor Day party when Judy Kaess, who lived nearby, asked him a favor. She’d inherited some old religion books from her father and wondered if he’d come by and look at them. By the time he’d arrived at Kaess’ house a few months later, she’d passed away of cancer. But her husband welcomed Prothero and led him to the family’s library.

Prothero thought he spend an hour looking at the books.

Ten years, later he’s still at it.

Those books — from legendary authors like Harry Emerson Fosdick, Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, Albert Schweitzer, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr and Bill Wilson, one of the co-founders of Alcoholics Anonymous — traced a history of American religion from the heyday of mainline Protestantism to the rise of the spiritual but not religious. The man who connected them all together was Eugene Exman, Kaess’ father and the longtime religion editor for Harper & Row, who had published them all.

Prothero knew he was on to something when he opened up a copy of “Strive Toward Freedom,” King’s 1958 account of the Montgomery bus boycott, and found a handwritten note from King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, thanking Exman for his help with the book. Then he found a similar note in a first edition of the Big Book of AA, this time from Wilson to Exman.

“Who is this guy that I’ve never heard of,” Prothero recalled thinking at the time.

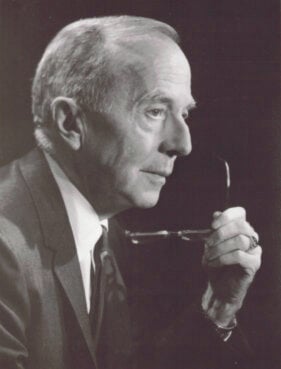

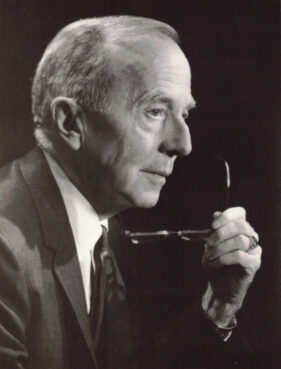

Eugene Exman passed away in 1975. Photo courtesy of the Eugene Exman Estate

That question sent Prothero on a search for Exman’s story and how the editor’s spiritual quest and knack for finding big ideas helped reshape religious publishing and American spirituality. He found the answers in a treasure trove of the Exman’s papers — stored in the family’s barn and file cabinets — including Christmas cards from Wilson and ethicist H. Richard Niebuhr, which Prothero rescued from a trash bag bound for the dump.

Those documents detailed Exman’s publishing career and his spiritual quests — which ranged from a boyhood encounter with God that haunted his life, to founding an ill-fated spiritual commune, to traveling to Africa to visit Schweitzer, to dropping LSD. Prothero tells that story in “God: The Bestseller,” due out March 14 from Harper One.

Prothero spoke with Religion News Service recently about the new book. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The book opens with the story of visiting the home of a neighbor and discovering what her father had left behind. When did you realize there was a book here?

When I first visited the house, I didn’t know why I was there. Usually, in a case like this, people want me to tell them what a collection of books like this is worth — and how to get rid of it. But Walter said, ‘No, no, no, we don’t want to sell the books. We want to give the books away.’ He said, ‘My wife has passed away recently. I’m worried that if I die, this stuff’s just going to end up in a yard sale.’

I started cataloging the books, and as I’m doing that, Walter keeps showing up with boxes, and I keep going through them. I got really curious.

It didn’t take long before I thought somebody’s got to write a book. And obviously, it was me. This was too perfect. I’m not really a providential or even a synchronicity person, but it felt kind of uncanny.

It almost seems like the universe decided you would be the one to stumble into this story.

Stephen Prothero. Photo by Meera Subramanian

Sometimes I did feel that way. But I also thought this is a really interesting book idea. And at first, it seemed the book was going to be about the authors. Then I sat down with a friend and former student for coffee and told her I had this archive and was going to write about it. But I didn’t think Exman was that interesting.

And she said, well, let me decide. Tell me about him.

So I told her about how when Exman was 16 or 17 years old, he was a fundamentalist, nerdy Christian-bookish kid. One night, he’s riding his horse to Bible study, and the horse all of a sudden stops and rears back in front of the cemetery. Exman looks up and he sees this light, and he feels this electricity going through him and he sees God. Then he kind of spends his whole life trying to make it happen again. He meets all the people who have had mystical experiences and they become his friends. Then they become authors and then their books become bestsellers.

She asked me, ‘Does he ever see God again?’

I say, ‘No, not really.’ And she says, ‘Oh, that is so good. I love it.’

That’s one of the questions I have about Exman. He never got what he wanted. Was he happy in the end?

I think he’s basically happy. But he never got what he really wanted. What he wanted was to have a mystical experience again and have it affirmed. He also really wanted to save the world from materialism and militarism, and he thought you could do that by publishing books. And when he died, he hadn’t accomplished that.

He had this friend, Marguerite Bro, who I write about a lot, who was always calling him to be a better person — to be a saint, as she put it. He knew he could not do that because he was too busy. He was a kind of organization man in that sense, and he just didn’t have time to be a 24/7 spiritual seeker. I think that he set a really high bar for himself, and he wasn’t quite able to get over it.

Albert Schweitzer, center, and Eugene Exman, right, during a trip to Africa. Photo courtesy of the Eugene Exman Estate

Let’s talk about the Rev. Martin Luther King for a minute. At the same time Exman was working on publishing “Stride Toward Freedom,” Harper is also working on a book about how much progress the country had made in racial reconciliation and how things are getting better. It’s quite a look into that time in American history.

That’s the whole environment Exman is swimming in at Harper in his religion books department — these are not milquetoast liberals. These are not liberals who think the world is just getting better and better. These are liberals who think you have to fight to transform the world. But Exman just sees race in this simplistic way. He thinks we all need to get along.

I just think it’s a good example of the tension between the kind of do-gooder white liberals that King writes about in his letter from a Birmingham Jail. And yet Exman published King and Howard Thurman, two of the most important authors in the civil rights movement. It’s complicated.

It seems like his skill as an editor was to have been taking these really, really important religious thinkers, preserving who they are and then translating them to the general populace.

He would just go get interesting people. He knew if he could find an interesting person, with interesting things to say, he could turn it into a book. He also had a real nose for what was going on for the zeitgeist of the culture.

Why does Exman matter? Why spend 10 years working on a book about him?

Eugene Exman. Photo courtesy of the Eugene Exman Estate

One of the big questions of our time is: Why is religion in such trouble in contemporary America? And why is spirituality doing so well? Why are there so many spiritual but not religious people?

I think Exman provides a genealogy of what I call the religion of experience, which is the most popular form of religion in the United States today. People see religion as a personal matter. They think it’s about feeling and experience more than it is about dogma or doctrine or ritual. They don’t think it takes place inside institutions. They think it takes place in the human heart.

How does that idea make its way into contemporary American consciousness? I think one big way is through the books that were published by Exman.

Even though he was a religious person who went to church every Sunday, he helped set up the society in which we are living. He undermined the religion brand. And he promoted the spiritual brand.