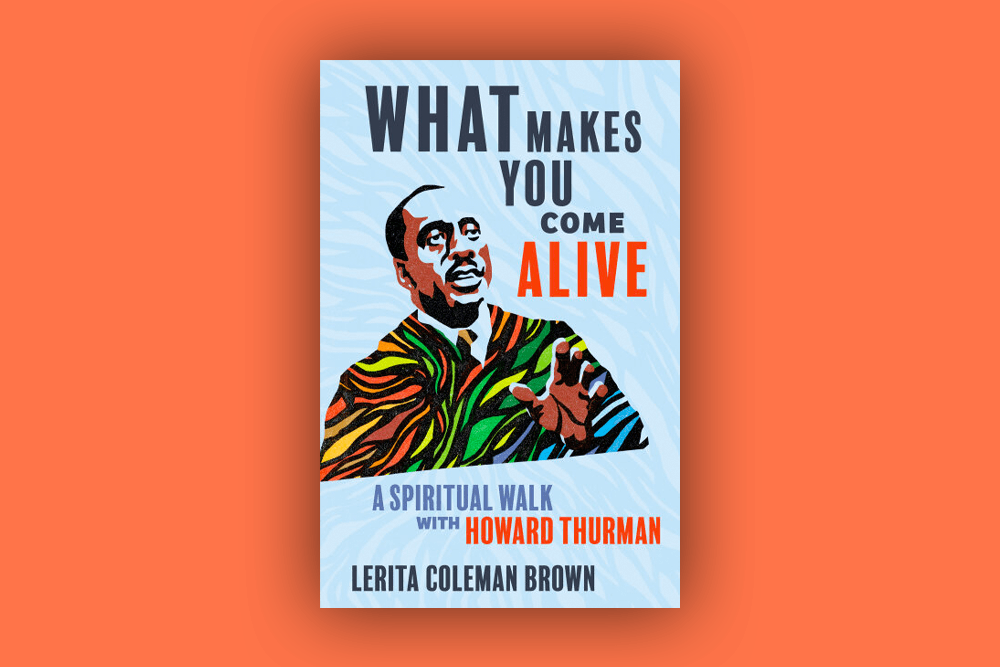

One may ask how to genuinely center themselves in the midst of police brutality, poisonous chemical spills, and constant war. As I began to read Lerita Coleman Brown’s new book What Makes You Come Alive: A Spiritual Walk with Howard Thurman, I received an overwhelming assurance that there was something to learn in this book about our turbulent and violent times.

Our starting point for this journey is a quote from mystic, theologian, and civil rights spiritual leader Howard Thurman: “Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive and go do that, because what the world needs is more people who have come alive.”

Brown gives readers an inside look into Thurman’s upbringing, personal details about his life, accomplishments, challenges, little-known stories, and how he impacted the world. This book presents a roadmap for a new generation of spiritual seekers and what Brown describes as “ordinary mystics.” As Brown notes throughout the book, those ordinary mystics are able to “quiet the surface noise enough to hear the meaning of all things coursing below daily life.” Ordinary mystics bring an “awareness of God” with them “into the emergency or operating room, the classroom, meetings, and courageous conversations.”

Brown begins the book with a story highlighting a spiritual encounter at the Wild Goose Festival years before writing the book. “It became evident that Spirit was issuing me an invitation to share what I had learned from Thurman. This book about Howard Thurman’s living wisdom is for spiritual seekers everywhere, and it stems from that call.” With transparency, she provides keys to unlocking the hesitancy and, often, misconceptions about spiritual care for everyday people. Brown offers helpful tools to reconstruct what the world tries to destroy: our spirits.

Through vulnerability and storytelling, Brown informs readers she did not learn about Howard Thurman until much later in her life and often found herself as the only Black woman in spiritual circles. “Throughout my adult life I had attended predominantly Black churches across the country, and I had participated in many spiritual retreats. But his name had remained absent from all those conversations.” She asks the question, “Why had I never encountered his work or been introduced to his writing?”

Thurman also spent the early part of his life questioning his spiritual encounters, searching for the answer to the question, “What makes you come alive?” Throughout the 10 chapters of Brown’s book, the focus revolves around silence, the natural world, inner authority, and distinguishing the religion about Jesus from the religion of Jesus, which places an emphasis on ministry to the marginalized. Today, that group includes “a wide array of marginalized individuals (such as people of color, women, and people with disabilities) as well as people of other faith traditions (Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist).”

Brown wants readers to understand that finding your center — to really dig deep to hear from the divine, and connect with your most inward thoughts, feelings, ambitions, and purpose — is accessible for all, regardless of church membership, religion, or socioeconomic status.

Brown bases her reflections on spirituality and Thurman’s life on one of Thurman’s most popular books: Jesus and the Disinherited Jesus and the Disinherited. Brown also relays unfamiliar stories about Thurman’s life to provide helpful background. One story in particular highlights the beginnings of Thurman’s educational journey. Because African American children in Daytona Beach, Fla., were only allowed to attend school to the seventh grade, Thurman’s community came together to ensure that he received private tutoring to attend high school. Brown illuminates moments like this in Thurman’s life to create a fuller picture of how a Black man facing unimaginable odds was able to maintain spiritual balance, offering honesty and hope for modern readers. “Even as a child, Howard realized he must master the sturdiness and rootedness of the oak tree to survive as a free human spirit in a world hostile to people who looked like him,” Brown reflects.

Regarding the civil rights movement, Thurman knew his role was to be a spiritual guide. Brown notes that “Thurman would sit with civil rights demonstrators and listen and pose questions rather than issue commands. He would ask them about what they were seeking and why and what means they utilized to achieve their goals. As a spiritual mentor, Thurman conveyed to them his firm belief that there could be no defeat of the movement if their motives remained oriented toward oneness.”

As demonstrated by his involvement with civil rights, Thurman’s emphasis on how humanity must tend to their physical and spiritual lives was important to his work, as well as a testament to those he directly and indirectly guided. The list of people Thurman influenced is expansive. Two activists that Brown specifically highlights are Martin Luther King Jr., and Pauli Murray who directly connected their spiritual lives to the physical struggle of humanity. By offering these examples, Brown gestures toward a pursuit of spiritual reconstruction, where people “walk together toward a reconstructed spirituality, remaining open to surprise gifts and knowing that we are not alone.”

Brown makes it clear that discovering and rediscovering what makes you come alive is a lifelong journey and not a one-time task. Life is difficult and the troubles of life can sometimes halt our journey toward the things that make us come alive. While direct spiritual approaches are not provided for dealing with trauma, she invites readers to pursue their own answers regarding spiritual development. Brown explains, “Silence, stillness, and solitude: in our noise-filled lives, these bring peace, heal, strengthen, and facilitate spiritual growth.”

But this invitation from Brown did cause me to pause and think: Is it really possible for every single person, especially those not afforded opportunities or whose silence is constantly interrupted by police sirens, environmental destruction, generational and systemic oppression to pursue what makes them come alive? In order to promote spiritual awareness sooner rather than later, I also asked myself: What might it look like to assist children and youth in underserved communities to take the steps outlined by Brown, helping them discover what makes them come alive?

In the midst of my questioning, I was reminded of Brown’s advice: “we may not be conscious that we are on a spiritual journey, but when crises and tribulations arise, a spiritual anchor is essential.” Perhaps the best way I can assist people who are not afforded practical opportunities to pursue the spiritual growth is to help them realize spiritual anchors can appear in unexpected places. This leaves open the possibility that opportunities for spiritual growth can appear anywhere.

Overall, this book invites us all to center ourselves, pay attention, and create space regardless of what is happening in our turbulent and violent world, never forgetting that what you hear in silence should fuel what you do out loud.