(RNS) — Julie Green had good news when she stood up to speak during the ReAwaken America Tour’s latest stop last week at the Trump National Hotel Doral near Miami.

God had told her that Joe Biden was on his way out, she said, according to videos of the event. And God’s people were going to win.

“We’re in the greatest battle for the soul of the nation this nation has ever been in since the founding of this nation,” said Green, an Iowa pastor known as a charismatic prophet and fervent supporter of former President Donald Trump.

God’s people, as Green’s theology makes clear, are her fellow Christians. And they would win, she added, because they would not give up: “You’re not quitting on what is rightfully yours,” she told the audience.

Green’s comments captured an essential element of Christian nationalism: The idea that America belongs to and exists for the benefit of Christians. Green’s fellow ReAwaken America Tour speakers — disgraced former Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, Roger Stone, Eric Trump and MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell, alongside pastors and prophets — are some of the loudest and best-known proponents of the ideology, which helped fuel Trump’s rise to the White House and has made national headlines since the Jan. 6 riot.

But its ubiquity, and the charge it carries in the current political debate, has made Christian nationalism a seemingly infinitely malleable term, one directed at times at anyone who supports Trump or any part of his agenda, and adopted by some who call themselves Christian and take patriotic pride in their country.

As a result, few people actually understand what Christian nationalism is, said University of Oklahoma sociology professor Sam Perry, co-author with Andrew Whitehead of “Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States.”

That doesn’t stop anyone from having an opinion about Christian nationalism, Perry said. “Either they’re very much for it or they’re very much against it.”

Samuel Perry. Courtesy photo

Perry argues that Christian nationalism is not a synonym for evangelical Christians. And not everyone who “votes their values” — a term often used by politically active conservative Christians — qualifies as a Christian nationalist. Nor do people who want religion to play a part in public life, he said.

Perry and Whitehead have defined Christian nationalism this way: “a cultural framework that blurs distinctions between Christian identity and American identity, viewing the two as closely related and seeking to enhance and preserve their union.”

In an interview, Perry contrasted that view with “civil religion”— when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. invoked the promises of the Declaration of Independence or President Barack Obama led a grieving congregation in singing “Amazing Grace.” These moments combined spiritual ideas and political moments.

Christian nationalism, Perry said, is more about who should be in charge.

“The difference between Christian nationalism and civil religion is Christian nationalism says this country was founded by our people for a people like us and it should stay that way,” said Perry.

In order to see how many people subscribed to this idea, Perry and Whitehead looked at data developed for the 2017 Baylor Religion Survey, which asked Americans to respond to statements such as “The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation” and “The federal government should advocate Christian values.” The Baylor researchers also asked about prayer in school and the separation of church and state.

In an interview, Perry said that some of the Baylor questions were a start, but the answers they yielded were too vague. He and Whitehead, along with other researchers, have fielded several national surveys in the past two years that Perry said have helped differentiate Christian nationalism from other, adjacent beliefs.

In 2022, the Pew Research Center found that 60% of Americans surveyed agreed the nation’s founders intended the country to be a Christian nation. Forty-five percent agreed the U.S. should be a Christian nation. But even among those who say the country should be a Christian nation, only about a quarter said the country should be declared a Christian nation (28%) or should advocate for Christian values (24%). About a third said the government should stop enforcing the separation of church and state.

A recent survey from the Public Religion Research Institute found that 10% of Americans embrace Christian nationalism, while an additional 19% are sympathetic to its ideals.

Paul Djupe. Courtesy photo

Paul Djupe, a political scientist at Denison University and co-author of an upcoming book called “The Full Armor of God,” recently retested some of the Baylor survey questions with some modifications. He wanted to know, for example, what people meant by America being a Christian nation and what it means to promote Christian values.

Does the latter mean promoting a more just society or one that sees everyone as made in God’s image? Does it mean values like loving your neighbor? Or does it mean enforcing Christian views over other views?

When Djupe modified Baylor’s statement “The federal government should advocate Christian values” to add “for the benefit of Christians,” he found there was little drop-off in support for that statement, leading him to suspect that those who support that statement had a more exclusive view of those values.

His survey also asked people to respond to the statement: “The Church should have a final say over whether legislation becomes law in the U.S.” Those who supported such a veto correlated highly with those who scored high on Baylor’s Christian nationalist scale.

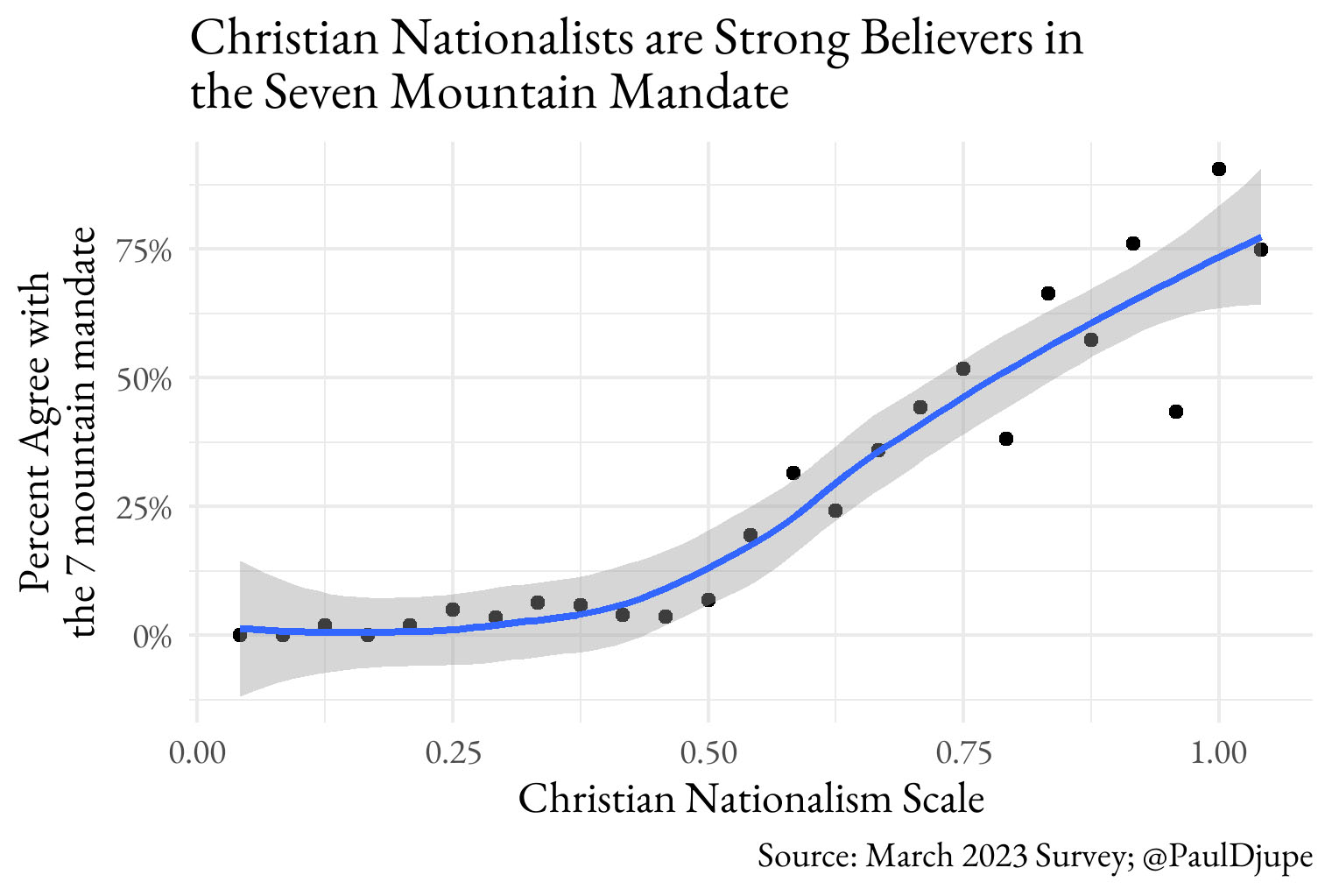

Djupe found enduring support for a doctrine known as the “Seven Mountains Mandate,” which claims Christians should rule in seven sectors: home, religion, schools, business, media, entertainment and government.

The idea was popularized by leaders such as Bill Bright, founder of Campus Crusade, a prominent evangelical campus ministry now known as Cru, and Loren Cunningham, longtime leader of Youth with a Mission, whose “7 spheres of influence” echoed the seven mountains.

“Christian Nationalists are Strong Believers in the Seven Mountain Mandate” Graphic courtesy of Paul Djupe

It was later adopted by charismatic leaders such as Lance Wallnau, known for his prophecies that Trump was God’s anointed.

“It’s like king of the mountain, only with much higher stakes,” said Djupe.

Matthew D. Taylor, a Protestant scholar at the Institute for Islamic-Christian-Jewish Studies in Maryland, says that the idea of dominion over all areas of life is central to what he refers to as Christian supremacy, a term he prefers to Christian nationalism.

Christian supremacy, he said, is more about Christians ruling over others. Taylor, creator of the “Charismatic Revival Fury” podcast series, which looks at the role charismatic Christian beliefs played on Jan. 6, pointed to prophets such as Green, who supported Trump because God told them who he wanted to be president.

“That’s deeply anti-democratic,” he said. “You can say, God has appointed this person. But that is not how democracy works. “

Taylor said that existing research into Christian nationalism is concerned with beliefs about the history and identity of the United States, but it misses the idea that “Christians should be privileged in society and should exert a coercive effect on society.”

“I think a lot of times people are trying to say, ‘America was founded with Christian values and these things are embedded within the essence of America,’” he said. “But it doesn’t say much about policy.”

In this Jan. 6, 2021, file photo, a man holds a Bible as Trump supporters gather outside the Capitol in Washington. The Christian imagery and rhetoric on view during the Capitol insurrection are sparking renewed debate about the societal effects of melding Christian faith with an exclusionary breed of nationalism. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Sarah Posner, a journalist and author of “Unholy: Why White Evangelicals Worship at the Altar of Donald Trump,” recalled seeing Christian nationalist themes in 2011, at the Response, a God and Country prayer rally organized by then-presidential candidate Rick Perry. “It was definitely ‘we need to take back America,’” she said.

But before the Trump era, that meant using democratic means. Since 2020, Posner said, the focus has been on rejecting the results of elections. “Before Trump, no one had permission to stage a coup.”

She said that the arguments over specific definitions of Christian nationalism can overshadow the movement’s main focus, which is power.

“Christian nationalism is not a pejorative. It is a description,” she said. “They have said that America is a Christian nation. How much clearer do they have to be?”

Julie Ingersoll. Photo via Twitter

Julie Ingersoll, professor of religious studies and author of “Building God’s Kingdom: Inside the World of Christian Reconstruction,” pointed out that Christian nationalists don’t necessarily share a single theology. Influential religious figures such as R.J. Rushdoony and other conservative social and political activists known as “reconstructionists” have long believed that Christians should have dominion over the world. But their theology is different from that of charismatics like Julie Green.

“It’s fluid and messy,” she said. “People want to make it neat and clean and divide these groups up and put them into little boxes with labels on them. Because that is more comfortable.”

But Ingersoll said religious differences between Christian nationalism and the broader evangelical movement are less important because, she argues, both are as much political as they are theological.

Still, she stresses that when Christian nationalists say that their candidate or party was chosen by God to win, they really mean it. And they may not be willing to let democracy get in the way of God’s will.

“The niceties of democracy fall by the wayside when you are on God’s side fighting Satan.”

This story was reported with support from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.