Art has always been a part of my life. It has also always been a quest to see God. My father was an amateur folk artist — think Grandma Moses — and always encouraged me to go to the museums in our hometown of Washington, D.C. Our favorite was the Phillips Collection, the first American museum of modern art. Picasso, Hopper, Degas are all there. These masters formed my consciousness from an early age.

We were also a Catholic family, which meant there was a direct connection between Christ and the beauty of art. The Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end, Christ to me could be found in everything from early cave paintings (Chesterton points this out in The Everlasting Man) to abstract expressionism. God created not just animals and beautiful women, but the clean, even, modernist line on the horizon that is so striking when one is standing on a beach.

God is definitely present at Glenstone, a museum in Potomac, Maryland, that I just visited. Set on 300 acres of tree covered hills, as one writer put it, Glenstone “blends art, architecture, and landscape design in a way that encourages visitors to turn off the noise of the digital world and connect with what’s in front of you.” There are magnificent sculptures, gorgeous paintings, works of neon and more unclassifiable art, and beautifully landscaped paths. The current main exhibit is the artists Ellsworth Kelly, a decorated World War II who studied art in Paris.

My Father and His Paintings

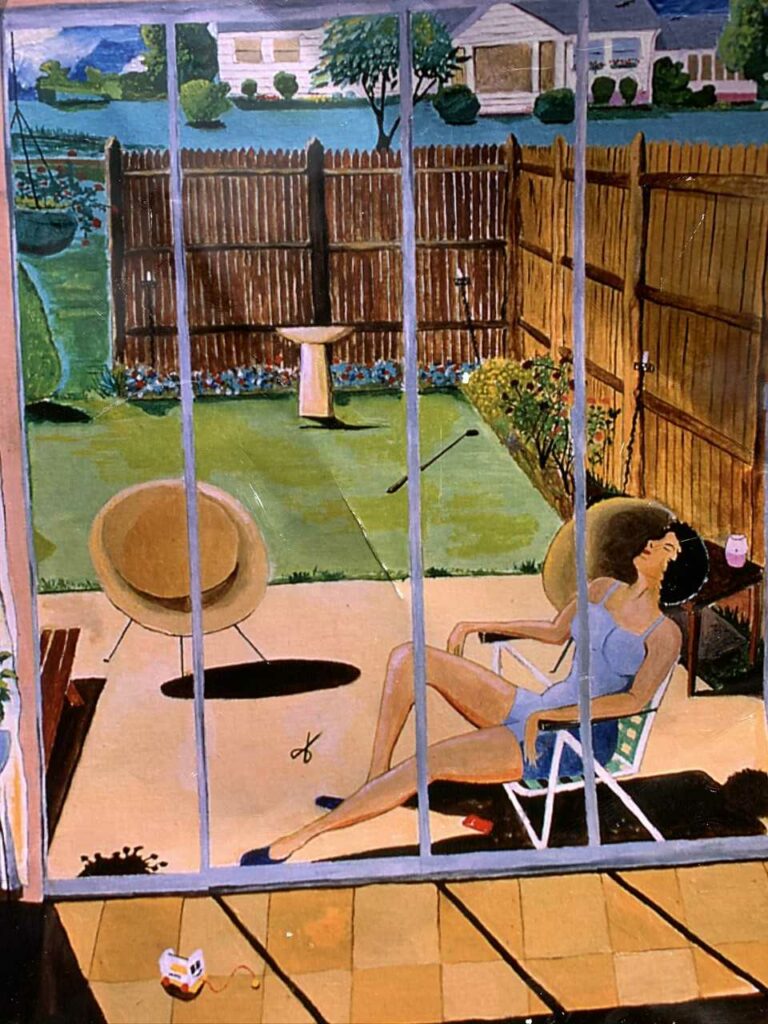

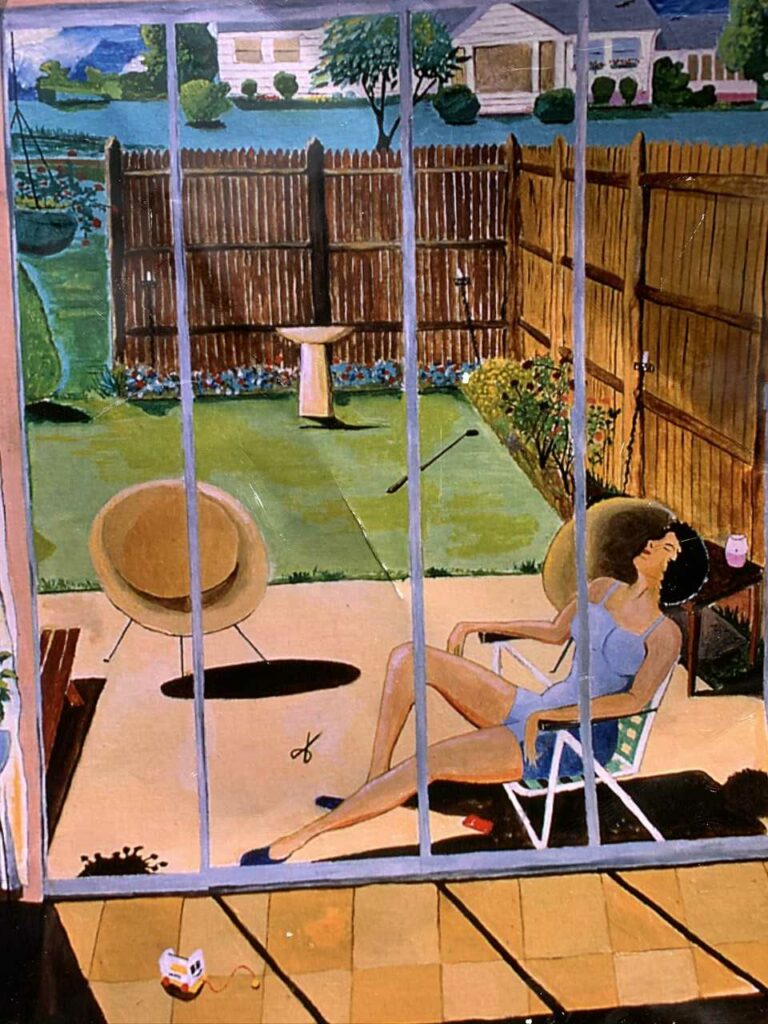

I spent an entire day at Glenstone. The museum is just a short distance from my childhood home in Maryland, and it made me think of my father and his paintings. Most of dad’s painting are of social events around our neighborhood — a block party, Halloween, the ice cream truck surrounded by kids. My favorite is from the early 1960s. It’s a summer view out the back of our house, with my mother sunbathing in the lower right hand corner. Again, this is folk art, not Andy Warhol or Georgia O’Keefe. Still, the painting lets me feel mom and dad in my soul the way a photograph can’t.

Glenstone is absolutely beautiful, reminiscent of the holy acres of a monastery. Spending time there gave me hope that art and beauty and God can bring Americans together. Too many conservatives have a distaste for even the idea of modern art, and too many liberals have defended awful and blasphemous art for too long.

The Art of Emptiness and Evil

Conservatives think most art today is all pornographic left-wing junk. They have been given good reason to think this. In 2016 it was revealed that the art collection of DNC officials Tony and John Podesta was bizarre and evil. The Podesta’s collection contained, as critic Michael J Pearce described it, “weird genetically-mutated piggy-children sculptures and creepy photographs of men with children running away.” People were “shocked to learn that this pillar of the Democratic Party owned a sculpture of a decapitated naked woman whose pose closely resembled a photo of one of Jeffrey Dahmer’s victims. Another installation in [Podesta’s] home included hyper-real sculpted hybrid human and pig figures, including piglet children.”

Pearce goes on: “suddenly, a powerful perception of a sick relationship between left-wing politics, avant-garde art, and pedophilia was established by media outlets covering the story.”

This stuff offended both mainstream and left-wing democrats: “Intersectional Democratic Party members were horrified that the taste of Podesta — one of their elite leaders — could include such offensive things. Party leaders seeking the middle-class vote were appalled at the offense to bourgeois values. The sculpture of the beheaded woman clearly offended feminist factions.”

How the Left Turned Against Creativity

Pearce saw this as one factor in the undermining of liberalism as the historical champions of great and modernist art. The other was how the left have become philistines.

Instead of supporting art, left-wing intersectional activists have become busy iconoclasts, calling for the destruction of a painting of Emmet Till, throwing paint at public sculptures of Columbus and civil war monuments, spray painting slogans onto the iconic “Unconditional Surrender” statue in Sarasota. There’s nothing particularly new or exciting about iconoclasm, but it is unusual that the political motivation of these activists is leftist, because supporting artistic freedom of speech had been the default position of the American left since the Second World War.

In his book The Triumph of Modernism, the great art critic Hilton Kramer argues that when modernism emerged in the 20th Century, the more conservative middle class embraced it. Housewives and normal Joes liked Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler, Odd Nerdrum and Alex Katz. Kramer, one critic observed, “insisted upon Modernism as an essential component of bourgeois culture.

Kramer admires Modernist art and has less patience for the artworks made after Modernism, which he tends to interpret in terms of decline or degeneration.” Contemplating Matisse’s work, Kramer observed, “It is hard to believe that we shall ever again witness anything like it, now or in the foreseeable future.” Today, instead, we endure “the nihilist imperatives of the postmodernist scam.”

What We Gain from Appreciating Art

If conservatives, perhaps buoyed by a space like Glenstone, can once again give art a chance, liberals for their part can reject the censorship and angry provocations of the far left. They might even begin to see and feel Jesus Christ, as I did, in a place like Glenstone.

The last piece of art I saw on my visit was Yellow Curve by Ellsworth Kelly. It’s exactly what it sounds like — a gigantic yellow curve made out of a kind of plywood and laid out gracefully on the floor. I loved it. I struck up a conversation with the young docent, who, like all the workers at Glenstone, was friendly and very knowledgable. I told her I had grown up just down the road and that my father did paintings about stuff we did growing up. Excitedly, she asked if I had any on my phone. I do. I pulled up the one of the backyard with mom sunbathing.

She absolutely loved it, and started telling me about what she, an educated art student, saw in the work — perspective, light, colors form the Kennedy era, and the female form depicted tastefully as art. I found myself putting hand to my heart. The docent is originally from San Francisco. A young woman, she has dark hair with some red in it. She confirmed when I asked that she was interested in both art and punk rock.

Here we were, two people undoubtedly on separate sides of the issues tearing American apart. Yet in this sacred space we were agreeing on the fundamentals — art, family, love, and how they connect us to something greater. I cannot give up on the country after that.

Mark Judge is a writer and filmmaker in Washington, D.C. His new book is The Devil’s Triangle: Mark Judge vs the New American Stasi.

React to This Article

What do you think of our coverage in this article? We value your feedback as we continue to grow.