(RNS) — Researchers at Cambridge University have discovered a document bearing the handwriting of the 12th-century rabbi, doctor, philosopher and polymath Moses Ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides, the university announced last week.

The 900-year-old “scrap of paper,” Cambridge said, was among the hundreds of thousands of fragments collected from the Cairo Genizah, a trove of Jewish writings held in a Cairo synagogue that collectively chronicles nearly two millennia of Jewish life in Egypt, where Maimonides, born in Spain in 1135, died.

It was first discovered in 2005, though its author was not known at the time. The writing was identified as the work of Maimonides by José Martínez Delgado, a visiting scholar from the department of semitic studies at the University of Granada.

Most famous for his comprehensive commentary on the Torah and Talmud, his compendium of Jewish law, the “Mishneh Torah,” and a philosophic tome, the “Guide of the Perplexed,” Maimonides wrote almost entirely in Hebrew or Judaeo-Arabic — an Arabic dialect written in the Hebrew alphabet with many Hebrew or Aramaic phrases.

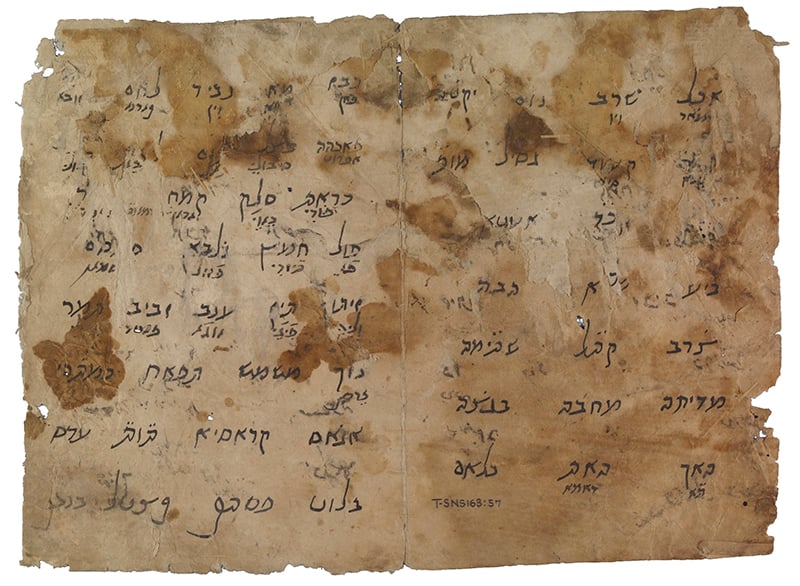

The page is a glossary written in the Hebrew alphabet but contains translations of more than 90 words into a pre-Spanish language known as Romance.

Maimonides was born in Cordoba, in what is today southern Spain but known at the time of his youth as Al-Andalus under the rule of the Almohad Caliphate, a North African Berber dynasty. The main language of the southern Iberian peninsula was Andalusian Arabic, though speakers of an Arabic-influenced version of Romance survived throughout the several centuries of Muslim rule.

Until now, however, there was no evidence that Maimonides, who left Cordoba in his early teens for Morocco and eventually Egypt due to Almohad persecution, had any knowledge of Romance.

Two pages now attributed to Maimonides in which he has listed words in Judaeo-Arabic and given Judaeo-Romance translations beneath. Photo courtesy Cambridge University

According to Sarah Stroumsa, a professor of Arabic at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and the author of “Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker,” the finding may help solve a mystery that has long surrounded the rabbi.

“The years between the time that Maimonides’ family had to leave Cordoba and their re-surfacing in Fez are somewhat of a black hole in the family’s history,” Stroumsa told Religion News Service. “It has been suggested that, like other Jewish refugees of the Almohad persecution, they moved north, to Christian Spain. In a roundabout way, Maimonides’ acquaintance with Romance would substantiate this possibility.”

Stroumsa cautioned that the newly identified writing doesn’t confirm this possibility and that Maimonides may have encountered Romance elsewhere.

Like Maimonides, Martinez Delgado was born in Cordoba, and his interest in the Genizah archive, as well as Hebrew and Judaeo-Arabic, stemmed from his interest in understanding the history of his own hometown, and the Jewish and Muslim communities that lived there before the Spanish expulsion in 1492, he told RNS.

Delgado had looked at the page before but thought nothing of it, but he came back to it this fall for a book he is working on about the history of the Andalusian Jewish community.

“Something about the handwriting in these Cambridge fragments seemed familiar. At last, I realized what I was looking at. I had seen this handwriting before,” Delgado said in the statement released by Cambridge. He sent the letter to a colleague at Tel Aviv University to confirm his suspicions. “I didn’t say what I was thinking — I just asked him to look at the fragment, too. Then came confirmation of my suspicions,” Delgado said. “We were looking at Maimonides’ handwriting, in some sort of Romance dialect.”

They ultimately used handwriting analysis methods to compare it with other documents from the Genizah that contain Maimonides’ signature and confirm that the document was his work.

To say that he was stunned would be an understatement.

“I was shocked. Because it’s not the first time that I found an unknown text, but this was the first time that it was an autograph — and this was Maimonides,” Delgado told RNS. “The feeling was overpowering.”

Researchers review documents attributed to Maimonides at Cambridge University in Cambridge, England. Photo courtesy José Martínez Delgado

Most interesting to him, however, was the insight the text gives into the thought process of one of the greatest minds in Jewish history.

The 92 words are grouped into four categories — colors, foods, flavors and scents — and actions.

“There is an internal order,” Delgado told RNS. “So the first thing that we thought is that this was maybe a draft, maybe a way to write a chapter, maybe to teach. But then we realized this was Maimonides.”

Famously a doctor, he could have been learning the language for medical purposes, Delgado posited. Alternatively, he suggested, it could have been a hobby, or simply an act of nostalgia.

“Maybe he missed the land of his youth,” Delgado said.

Already 60 notes or page fragments from the Genizah have been identified as by Maimonides, who served as chief rabbi of the Egyptian Jewish community at the end of the 12th century.

According to traditional Jewish practice, holy documents, such as those containing the tetragrammaton or ineffable four-letter name of God, are meant to be disposed of in a respectful manner. Usually, they are saved by synagogues in a room known as a genizah and eventually buried in a Jewish cemetery.

The trove from Cairo’s Ben Ezra Synagogue was preserved for so long due to the city’s arid climate. Its significance was first identified by Rabbi Solomon Schechter, a founding father of Conservative Judaism who was then a professor at Cambridge.

“The documents of the Genizah are crucial to our understanding of Maimonides: the development of his thought as well as his biography, his social interactions, his place in the community and his emotions,” Stroumsa said. “The Genizah kept for us his personal correspondences, his responses, as well as fragments of drafts of several stages of his work.

“But perhaps even more important is all the rest of the Genizah, the documents and texts that are not connected directly to him,” she added. “The Genizah changed dramatically our ability to reconstruct the context (cultural, communal, social, religious and political) in which Maimonides lived and acted, a context which is essential for a correct understanding of his philosophic and halachic work.”