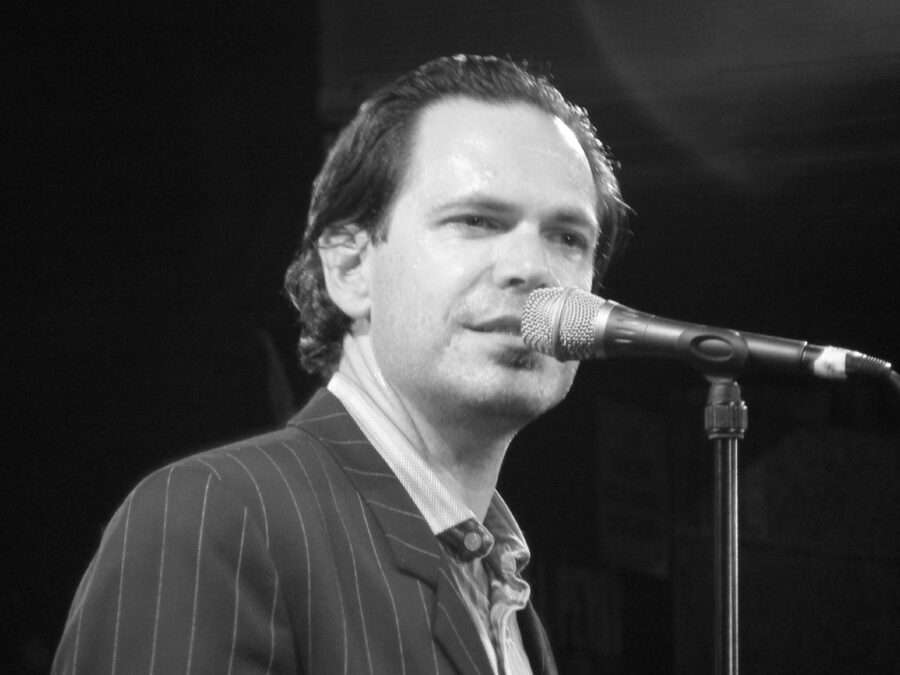

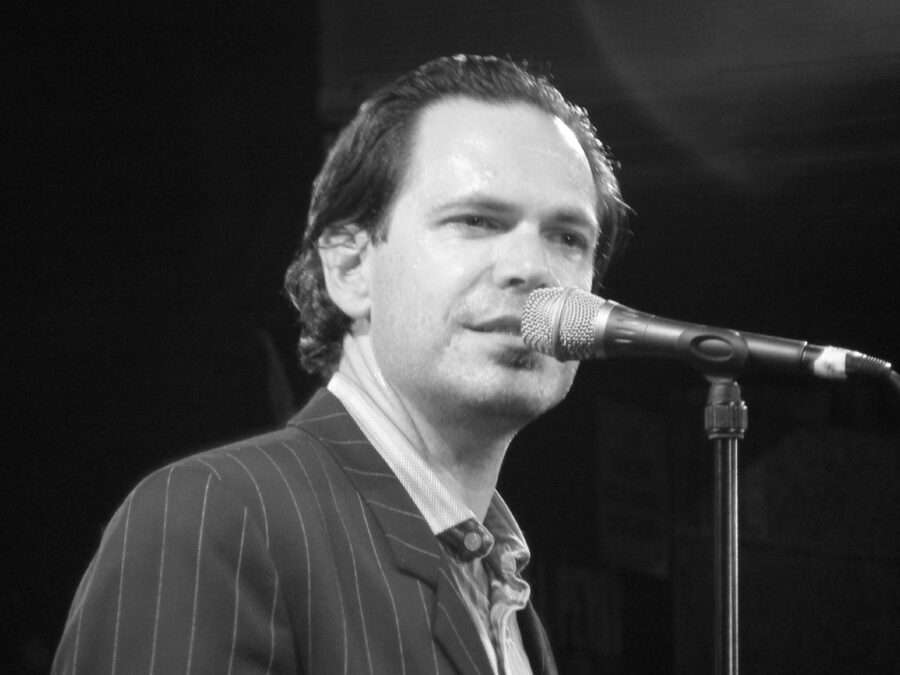

In the summer of 2006, I had a powerful spiritual experience. I was at a live concert in Maryland watching the great jazz singer Kurt Elling when Elling combined the romantic ballad “My Foolish Heart” with the poem “The Dark Night of the Soul” by Saint John of the Cross. Elling began with the pop standard:

The night is like a lovely tune

Beware my foolish heart

How white the ever–constant moon

Take care my foolish heart

There’s a line between love and fascination

It’s hard to see on an evening such as this

Then at the mid-point of the song, the band lowered the volume until there was just the steady beat of the drum. Elling began to chant in his five–octave baritone:

One dark night

Fired with love’s urgent longings

Clothed in sheer grace

I went out unseen

My house being all now still

On that night

In secret for no one saw me

With no other light that the one that burned in my heart

This guided me more surely than the light of noon

To where she waited for me

That Rare Thing: Genuine Art

It was St. John of the Cross. Elling was combining “My Foolish Heart” with the work of a 16th–century Christian mystic. It was that rarest of things these days: a genuine work of art. It was neither a call for dismantling age-old notions of sex and romance, nor a piece of salacious pop junk that would get millions of downloads.

America is still capable of art like Elling’s. The jazz scene is full of wonderful art. But the population is increasingly unable to appreciate it. Our minds and souls have been captured by politics and pop culture. In the best political book of the last ten years, The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, Polish scholar Ryzsard Legutko lays out a sobering case that modernism has reach a point where we are caught between two extremes. On the one hand is liberal utopianism, and on the other is infantile pop culture.

We All Live on a Conveyor Belt

Legutko’s thesis is that both liberal democracy and communism have a similar concept of time. Both view history as moving inexorably towards a utopia of perfect egalitarianism, health and tolerance, and that it’s the job not just of politicians but of all right-thinking people to facilitate that bright tomorrow:

What the enemy of progress defended was by definition hopelessly parochial, limited to one class, decadent, anachronistic, historically outdated, and degenerate; sooner or later it had to give way to something that was universal, necessary, and inclusive for of the whole of humanity.

Prior to the 1960s, there was a general understanding in the West that that role of politics was to create an environment where politics was largely irrelevant to ordinary people’s existence. The American Revolution posited that the role of government was to protect rights that existed prior to government itself — the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Freedom and Tradition, Together

Government existed to protect basic rights and allow a wide latitude of regional customs and traditions. This was evident from Calvin Coolidge’s hands-off approach to the presidency to JFK’s prudent incrementalism — allowing freedom and tradition while addressing problems and crises.

The Civil Rights movement was a call to abolish the idea that governments could tell people where they could go and who they could love based on race. It was a demand that the government protect the basic rights laid out in the Declaration of Independence.

America reached a cultural and political high point in the mid-20th century. In 1955 35 million people paid to see classical music concerts, and in 1956 NBC aired a three-hour Richard III. We were also beginning to address the sin of slavery and Jim Crow: Martin Luther King laid out the shame of our past, forcing Kennedy and then Lyndon Johnson to take measures to ultimately dismantle segregation.

Natural Law’s Last Victory

King made his case brilliantly in “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” observing:

There are two types of laws: There are just laws and there are unjust laws. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine that ‘an unjust law is no law at all.’

King concluded that

a just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas, an unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law.

Such an observation today would brand the author a religious fanatic by feminists and prevent him from running a business, holding office or appearing on TV.

The Last Flickering Light

We also had an acute sense of our mortality and that utopia is not possible on this Earth. Many more people dies of diseases and in wars. In a famous 1963 address, President Kennedy said: “For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.” That kind of humility is absent today, when people demand everything from the proper pronouns to eternal “transhumanist” life.

After the 60s, liberalism became about coercion and thought control rather than leaving people alone. “The revolution [of the 1960s] was not a triumph of classical democracy, but an explosion of livid impatience directed at the discipline of the democratic system,” Legutko writes. “Within a short period of time Europeans changed the perception of democratic politics and became convinced that it was about modernization, progress, pluralism, tolerance, and other sacred aims, which were to be carried out regardless of what the voters decide during elections.”

They Want to Control Us

Legutko brings the argument up to the present day:

Not only do [liberals] want to control the mechanisms of the great society but also those of all its parts; not only what is general but also specifics; not only human actions but human thoughts as well. The original message, ‘we will only create a framework of society at large, and you will be able to do what you want within it’ is rapidly turning into [an] increasingly detailed message such as, ‘we will only create frameworks in education (in the family, in community life) and you will be able to do what you want within them later.’ But even this is not enough: ‘We will only create a framework at this school and you will be able to do what you want within it later.’ Then the class follows the school and so on and so forth.

Politics now encroaches upon everything.

We Choose to Be Swine

Legato also laments our devolution into crudity—the fact that if given the choice “between being a pig and being Aristotle,” more and more Western people will choose the swine. In the last fifty years there has been transition in popular art from material that seeks to elevate the human soul to films, TV shows and music that not only insists on degradation but demands that anyone calling for a higher standard is a hypocrite.

In his book Notes on the Death of Culture, Mario Vargas Llosa drives to the heart of a devastating problem in the culture of the West: its total erosion . While culture can certainly be comic books, movies, and pop songs, we have increasingly lost sight of, and appreciation for, the more complex and challenging works of art that can more deeply change us.

Llosa cites books by T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Homer, and Nietzsche; works of art by Picasso, Rembrandt, and Seurat; and plays by Chekhov, O’Neill, Ibsen, and Brecht as examples of things that “enriched to an extraordinary degree my imagination, my desires and my sensibility.” I would add the work of jazz artists like Kurt Elling, John Coltrane and Chris Potter and the incomparable books of G.K. Chesterton.

We Don’t Want to Break a Mental Sweat

One thing all of these works have in common is the great effort it took to create them and the effort it takes to consume them, at least if we are to truly understand them. Great works of culture should change who we are. They should also attempt to engage with complex cultural and spiritual issues.

But with the democratization of culture, the digital revolution, and the elimination of middle and highbrow culture in favor of pop culture, this is no longer necessary. Llosa argues:

Now we are all cultured in some way, even if we have never read a book, visited an art exhibition, listened to a concert or acquired any basic idea of the humanistic, scientific or technological knowledge in the world in which we live.

Culture becomes not something that you have to actively work at — even as that work is intensely rewarding and joyful — but something you passively consume. Llosa admits:

Of course, culture can indeed be a pleasing pastime, but if it is just this, then the very concept becomes distorted and debased: everything included under the term becomes equal and uniform; a Verdi opera, the philosophy of Kant, a concert by the Rolling Stones and a performance by the Cirque du Soleil have equal value.

The Everlasting Man by Chesterton is not a Marvel superhero movie.

Becoming Perpetual Children

There have always been pop culture entertainments that have captured a society’s attention, from the circus to The Untouchables to Marvel’s string of hit superhero movies. I myself love pop culture, finding metaphors in the music of Taylor Swift or an epic like The Dark Knight Returns. (Llosa is also no snob, admitting he loves movies and goes to them twice a week.)

Yet what has been lost in the last few decades is a willingness by cultural consumers to do some heavy lifting and take on more challenging works of art: The Brothers Karamazov, Beethoven’s symphonies, difficult plays. Or, I would add, the writing on art and theology by Christian genius Dietrich von Hildebrand. Without such anchoring and altering works, Llosa argues, a culture becomes adrift, feckless, and childish. We now see grown men, many of them conservatives, arguing about Game of Thrones.

Despite our vast scientific and technical knowledge, Llosa argues:

We have never been so confused about certain basic questions such as what are we doing on this planet of ours, if mere survival is the sole aim that justifies life, if concepts such as spirit, ideals, pleasure, love, solidarity, art, creation, beauty, soul, transcendence still have meaning and, if so, what these meanings might be?

It’s Love, in the End

To me, the meaning of our life is clear, and was glorified beautifully that night in 2006 when Kurt Elling combined a classic love song with the prayer of a saint. We are here to love God with all our hearts. It is dynamic love that is rewarded with colors and shapes and sounds behind our counting and with endless depths of joy. It is, as St. John said, “the love that awakens love.”

Llosa’s critique offers a challenge and a warning:

The raison d’être of culture was to give an answer to these questions. Today it is exonerated from such a responsibility, since we have turned it into something much more superficial and voluble: a form of entertainment or an esoteric and obscurantist game for self-regarding academics and intellectuals who turn their backs on society.

In other words, culture should not merely be passive entertainment, but an active (and often edifying) journey toward a better understanding of what it means to be human. Without God at the heart of the inquiry, politics becomes an idol and pop culture becomes garbage. Decline is inevitable, unstoppable.

Mark Judge is a writer and filmmaker in Washington, D.C. His new book is The Devil’s Triangle: Mark Judge vs the New American Stasi.

React to This Article

What do you think of our coverage in this article? We value your feedback as we continue to grow.