(RNS) — Former British Prime Minister David Cameron once quipped that his religious convictions came and went like World War II-era radio’s patchy reception in the countryside. That is not a bad characterization of the British government’s relationship with the country’s faith communities as a whole.

Not that prime ministers have not made sincere efforts to connect with people of faith in the United Kingdom. Cameron’s coalition government did much to strengthen faith engagement, not least the creation of a Minister of Faith tasked with promoting religious tolerance, and the appointment of a special envoy for religious freedom.

More recently, the British government launched something called the Faith New Deal — a pilot project funding partnerships between local councils, schools and faith organizations to build stronger communities.

In 2019, then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson asked me to do a pangovernment review into how it engages with faith. Perhaps his instinct was that the gap between government and faith was just too wide, too disconnected. As it turned out this instinct was spot on.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I set up faith roundtables that brought government and faith leaders together in a meaningful two-way relationship. Faith communities worked with the British government on negotiating and implementing COVID-19 guidance for places of worship and finding ways of engaging with harder to reach communities. Amid the turmoil of the pandemic, some groundbreaking work was done.

But despite all this brilliant partnership working during the pandemic, there is a prevailing sense that central government is not entirely comfortable with meaningful faith engagement.

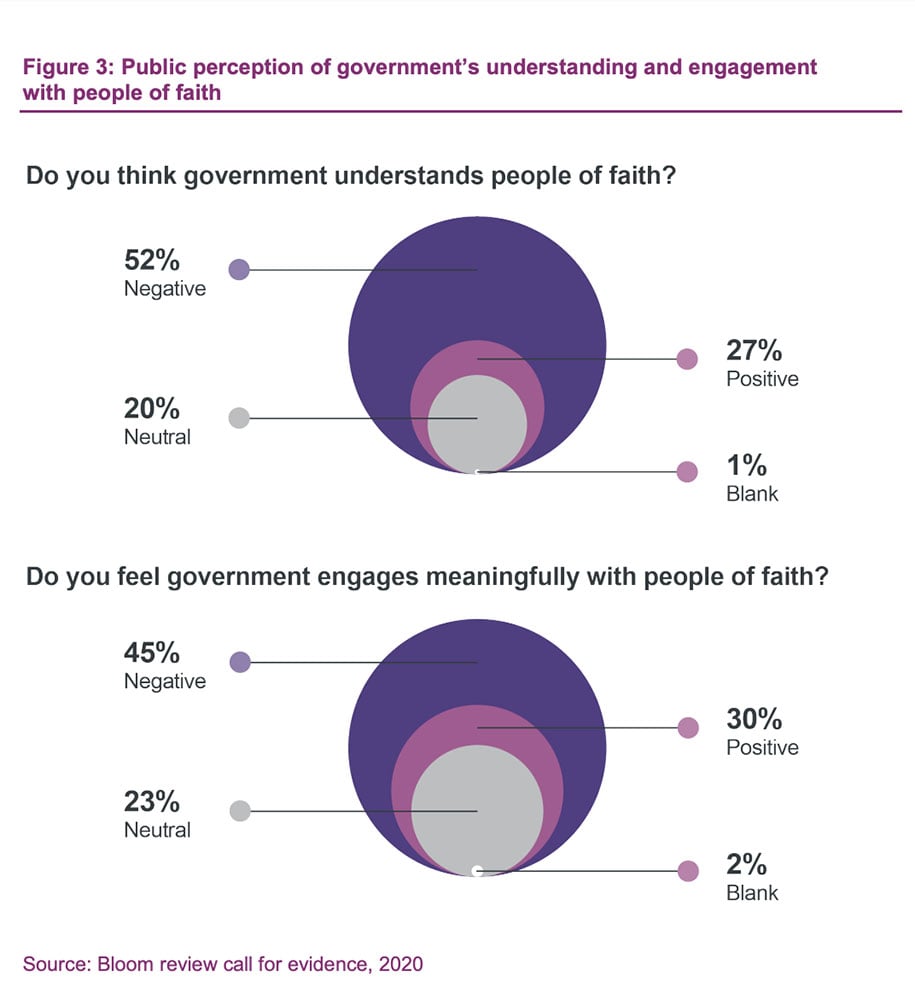

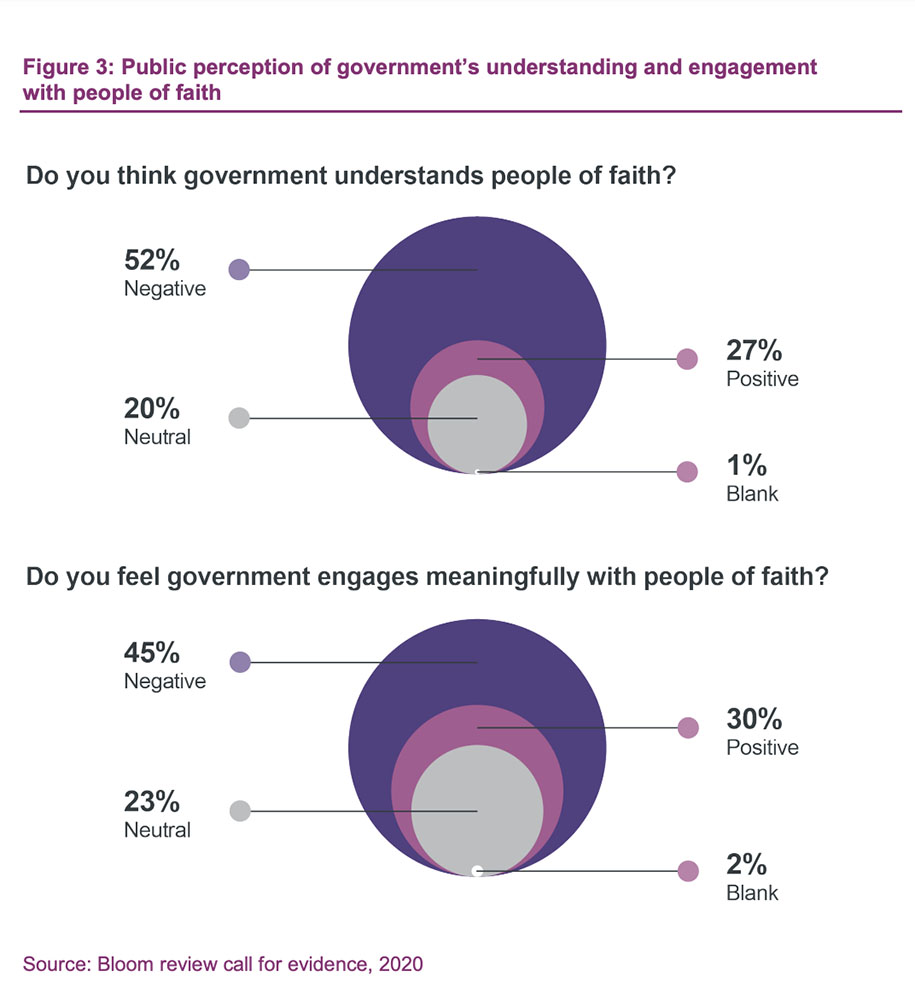

“Public perception of government’s understanding and engagement with people of faith” Graphic courtesy of Colin Bloom

Since 2021, for instance, these roundtables have all but stopped. This perpetuates the persistent view among many faith communities that they are not trusted, lifelong partners of government, and that politicians and Whitehall only get in touch when they want something.

Understanding why this is the case was among the key aims of my review into how government engages with faith groups.

Two years ago, as part of the review, I launched a public “call for evidence,” and it’s fair to say that there was some surprise at the scale and enthusiasm of the reaction. With more than 21,000 detailed responses, it was possibly one of the largest responses for such a call the British government had ever had.

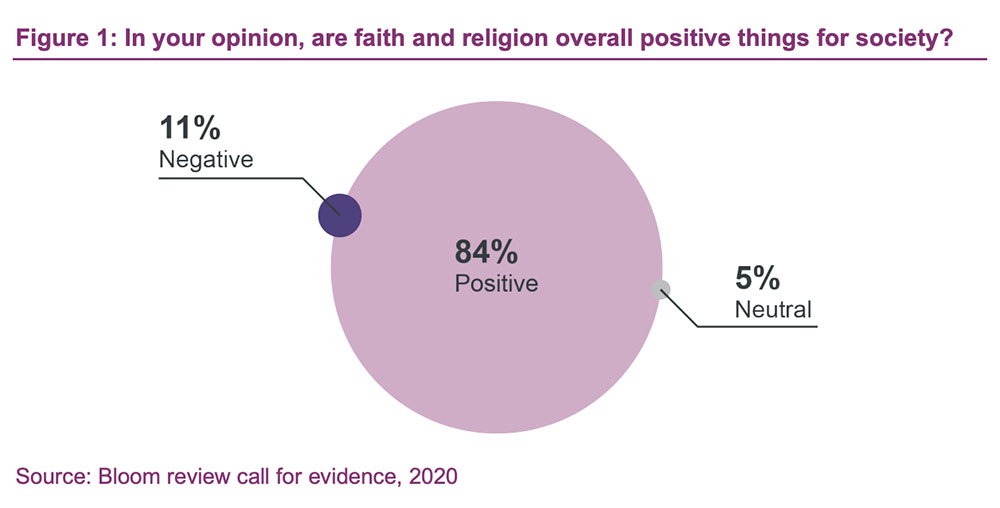

We should not have been surprised. As in the United States, faith-based groups and places of worship play a crucial role in strengthening the ties that bind our respective countries together. For millions of people, their faith informs who they are, what they do and how they interact with their neighbors.

From running schools and toddler groups, to food banks and tackling loneliness, without our places of worship much of local, everyday life would simply fall down. The overwhelming majority of places of worship are “schools of virtue” — helping people become the very best versions of themselves.

Across the world, in the United States and in the U.K., faith continues to matter to the majority of our people and, as a force for good, it should matter much more to governments than it currently does.

“In your opinion, are faith and religion overall positive things for society?” Graphic courtesy of Colin Bloom

So, what needs to change?

My review sets out 22 recommendations to strengthen the government’s understanding of and relationship with faith, people of faith and places of worship.

At the heart of these recommendations is a much-needed program of faith literacy training for all public sector staff, from the civil service and the armed forces to schools and prisons. The 2010 Equalities Act listed nine protected characteristics; the evidence would suggest that faith is the Cinderella of this particular story. It needs a Prince Charming government that will take faith to the ball.

Such a program would ensure that public servants at every level understand those they serve and can more readily engage with groups that are already doing so much to strengthen the social fabric of our society.

Other recommendations are designed to tackle the relatively few but sometimes devastating faith-based harms.

The report calls for a greater effort in tackling faith-based extremism; stopping people becoming so isolated from the country in which they have been born or brought up that they fall prey to radicalization and violence. There is a section on Islamism, white supremacists and neo-Nazis, Sikh extremists and Black supremacists. While great progress has been made on tackling the first two, other forms of faith-based extremism have grown under the government’s noses.

The review calls for root and branch reform of how government tackles the terrible plight of people coerced or forced into marriage, the vast majority being women and girls.

Underscoring all these recommendations, however, is one constant theme: Government needs to be bolder, more discerning and more open to faith engagement.

It must do the hard work of building relationships with genuine faith leaders, and it needs to raise its game on understanding faith, interfaith and intrafaith issues.

If it does, not only will public services be delivered more efficiently and effectively, but the U.K. will become a better place to live for the majority of the public who still say that they have a faith.

(Colin Bloom is an independent adviser to the U.K. government. He has previously been a director of the U.K.’s Conservative Party and its international secretary. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)