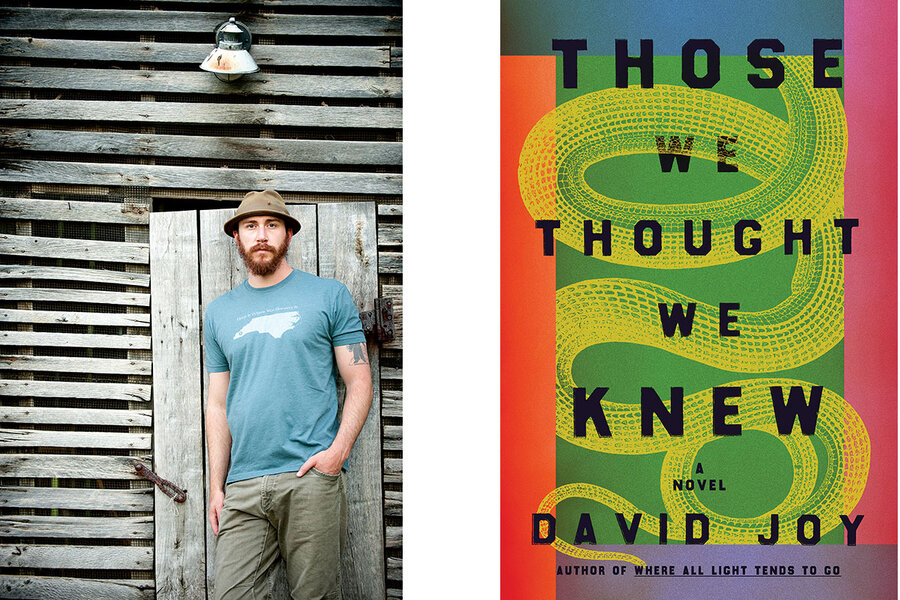

Novelist David Joy has mastered the high-stakes, page-turning Appalachian-noir style, and through this lens, he overturns preconceived notions of life in the mountains.

In his latest book, “Those We Thought We Knew,” Mr. Joy weaves a tale of a young Black artist returning to her ancestral town in the mountains of western North Carolina, and the subsequent arrival of a Ku Klux Klan member who is found passed out in his car. The police find evidence not only of his klan ties, but also a notebook with the names and phone numbers of county officials.

Mr. Joy spoke with Monitor contributor Noah Davis about his family’s legacy in North Carolina, and about the beauty of the noir genre: “Everything has been whittled down to its most essential. The masks are pulled back,” he says. “Creating a story that strips a time and a place and a people to its bones allows the reader to see it for what it truly is.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

A novelist with deep regard for his fellow North Carolinians delivers a clear-eyed critique of the blindspots of the South – both past and present.

In his unflinching and timely novel “Those We Thought We Knew,” author David Joy weaves two storylines: the return of Toya Gardner, a young Black artist from Atlanta, to her ancestral home in the North Carolina mountains, and the subsequent arrival of a high-ranking member of the Ku Klux Klan. The man, passed out in his car from inebriation, is discovered by local deputies. Also inside the car is an incriminating klan robe and a notebook filled with county officials’ names and phone numbers. A still-standing Confederate monument at the town’s center sets the stage on which the community will fracture. Unspoken sentiments are suddenly shouted, and shrouded fears and hate come into the light. Mr. Joy has mastered the high-stakes, page-turning Appalachian-noir style, and through this lens, the preconceived notions of life in the mountains are overturned. He spoke recently with the Monitor about North Carolina and the stories that must be told – the same stories that were purposefully hidden.

All five of your novels are set in the mountains of western North Carolina. It’s easy to see how much you admire the beauty and people of that place through your attentive sentences. What does it mean to love and critique a place at the same time?

I think what you’re getting at is what the [rock band] Drive-By Truckers referred to as the “duality of the southern thing.” I speak proudly about being a 12th-generation North Carolinian. My first ancestor comes into what becomes Bertie County in the late 1600s. But the truth is that you can’t make that sort of statement without acknowledging and accepting the horribleness that so much of that history entails. There’s this balancing act of being tied to a place and a people with that sort of past. So to slightly alter something James Baldwin said, “I love [the American South] more than any other [place] in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

A novelist with deep regard for his fellow North Carolinians delivers a clear-eyed critique of the blindspots of the South – both past and present.

Can you talk about what makes the noir genre a compelling style to examine the complex issues around race and history?

I was on a panel with [crime novelist] Megan Abbott once at a festival in Vincennes, [France,] and she said, “Noir lends itself to the social novel.” Everything has been whittled down to its most essential. The masks are pulled back. Creating a story that strips a time and a place and a people to its bones allows the reader to see it for what it truly is. As a country, we’ve reached a place that offers little space for civil discourse. Art allows for that space. It allows for us to be made uncomfortable, to sit with ideas that challenge us, and to do so without choosing a side, without consequence.

This is a novel of questioning and upending expectations. How much was this book an act of discovery for you about the people and place of your home?

I don’t think I consider anything about this book an act of discovery. When you’re dealing with matters of white supremacy, and particularly dealing with Black suffering and trauma and death at the hands of that institution, one of the hardest things to stomach is the cyclical nature of it all. America is stuck in a feedback loop. And the sad truth is that in 2023, we know the defect in the code, and yet we continue to do nothing about it. Take that a step further, and I think that Americans, and particularly white Americans, have a false belief that if we don’t talk about it, it will just go away. We refuse to have the hard conversations. We refuse to address the defect. This book was an attempt at forcing characters into those conversations.

Because of those upended expectations, the reveal leaves the reader feeling unstable. But you’re still able to conclude with a moment of hopeful certainty. Why is that important to you?

There’s a scene in the novel where the grandmother, Vess, is in the garden with her granddaughter, Toya, and the old woman is humming a song while she ties up rows of beans. Toya recognizes the song and pulls it up on her cellphone to play it. The song is Nina Simone’s “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life.” To anyone who knows that tune, it begins as this sort of mournful elegy. But Vess notes that what she’s always loved is the turn, the moment when that lament of all that’s been stolen shifts into a celebration of what cannot be taken away. I wanted the ending of this novel to mirror that arc. Without that shift, we’re left standing in the same place we started. What moves the foot forward is hope.