(RNS) — How many checkpoints does it take to cross into Jerusalem from Amman, Jordan, on Christmas Eve to visit the Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock when Israel is waging war with Hamas?

Turns out, 24. And that was with a U.S. passport, which seems to make (considering the circumstances) a relatively easier time of it.

Here’s another question: What possessed my husband and me to take two of our three kids on a 24-hour trip into wartime Israel on Christmas Eve, when we are a visibly Muslim family, one of whom is a 16-year-old male? When Palestinian and/or Muslim males between the ages of 12-50 are often not even allowed into the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound and when, with tensions afoot, we are at the whim of the Israeli Operations Force?

The story begins long before Oct. 7.

Nearly four years ago, when our now college junior was still in high school, we had planned to go on pilgrimage — not the full hajj but the lighter-duty umrah — after her graduation. We were delayed by COVID-19, but last fall, my husband fixed on her winter break. Before visiting Medina and Mecca to perform our umrah (second-plus time for the adults, first time for our kids), we’d go to Jerusalem to visit the Dome of the Rock and Masjid Al-Aqsa — the third-holiest site in Islam after Masjid Nabawi, the Prophet’s mosque in Medina, and the Masjid Al Haram in Mecca, the site of the Kaba.

Hadith teaches Muslims that one “salah” (prayer) in Al-Aqsa is worth 500 prayers, one prayer in Masjid Nabawi is worth 1,000 prayers, and one prayer in the Haram is worth 100,000 prayers.

The Ali family in front of the Dome of the Rock on Dec. 24, 2023, in Jerusalem. Daughter Amal, from left, son Hamza, Dilshad and husband Taruj. (Photo courtesy Dilshad Ali)

In September, we found a Jordanian company, Taleen Tours, for our visit to Al-Aqsa. The next month Hamas attacked. We would still go to Saudi Arabia to do our umrah, but Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa? We monitored the war and mourned the horrific loss of life in Gaza and weighed our options.

In October I wrote about Palestinian, Arab and Muslim students (in addition to Jewish students) being targeted on college campuses. At home, I told my husband that we should drop the Al-Aqsa leg of our trip. But with our tour company still safely taking people into Jerusalem, he said, telling me, “Let’s see how things are once we’re in Amman.”

We arrived in Amman late on Dec. 23. The next morning we set out with our guide, Mohammed Bishi, who would quickly become a trusted friend. Our first stop, in Jordan, was the gravesite of the Prophet Yusha, the biblical Joshua, Moses’ successor. At 10:30, after we’d said our prayers, Bishi informed us it was time to head to the King Hussein Bridge to attempt the crossing. Israel, he’d been informed, was closing the border by 11:30 a.m.

“We doing this?” my kids asked nervously.

“Um, I guess so,” I replied. Tamping down my rising anxiety, I asked my husband, “How is this working exactly?”

Bishi told us he would take us as far as the bridge, but we would be crossing through the border checkpoints alone. Once through, we’d meet our Jerusalem-based guide who would drive us to our hotel near the Old City.

The Ali family experienced a largely empty Al-Aqsa Mosque complex during their visit. (Photo by Dilshad Ali)

We had packed into backpacks to avoid luggage checks and other delays. I had ordered the kids to keep their comments to a minimum, not to ask questions (unless absolutely necessary), don’t talk back to the IOF officers at the border and follow our lead.

This advice echoed numerous discussions we’d had at home about the reality of what trying to visit Al-Aqsa would be like. My brother, a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon, had traveled into Gaza, the West Bank and Israel numerous times as a volunteer with Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund. He had schooled us on how confrontational the machine gun-toting IOF officers could be. He also said we should “look Muslim” — and even be prepared to recite something from the Quran — because only Muslims are supposed to worship at the Al-Aqsa complex.

He also told us that our 16-year-old, Hamza, may not be allowed in, because young Palestinians are seen as a threat. If any of us were detained, we had decided, none of us would move forward.

As we moved through checkpoint after checkpoint, sure enough, Hamza’s age was questioned. They also asked who my husband’s father was and if we knew anyone in Jerusalem. It seemed like an eternity of silent scrutiny as the guards stared at their computer screens. We held our breath and waited.

As we waited, the tour company sent a WhatsApp message saying the hotel where we were supposed to stay that night had shut down due to the “situation,” (everyone we met called the war “the situation” with simmering anger). We had been rebooked into another hotel, but we had no email proof of our reservation. Minutes later, the guards asked where we would be staying in Jerusalem.

My husband explained what had happened. “Show us your reservation,” the border guard said. My husband showed him the WhatsApp message. I thought the jig was up. After another forever, however, they allowed us through to the next checkpoint and the next after that. We finally found ourselves outside and officially in Israel.

Our guide on the Jerusalem side, a young Palestinian gentleman named Awadallah, picked us up. We learned that he and his wife were expecting their first child any day and that they were staying with his grandmother in Jerusalem.

“I own our own home in Bethlehem,” he told us. “But I haven’t been there in two months since the situation started. There were already too many checkpoints to get to my home. Now, there are even more. It can take four hours to get from my grandmother’s home to my home. It’s too dangerous, so we are staying with my grandmother until the baby is born.”

A guide leads the Ali family into the Old City of Jerusalem through the Herod Gate. (Photo by Dilshad Ali)

As we drove into Jerusalem, our excitement rose as we saw the dull gold of the Dome of the Rock far off in the distance. At our hotel, where we were the only visitors, our driver said they had made arrangements for the oldest guide they could find for our walking tour of the Old City and to take us into the Al-Aqsa complex, as no men under 50 were being allowed in.

Baghet, our 78-year-old Palestinian guide, had plenty of energy to go with his deep religious and historical knowledge. A retired school teacher, he had been giving tours for more than 40 years. He escorted us through the Herod Gate, past walls that date to the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman the Magnificent, into the Old City, where we encountered more geared-up IOF guards.

Baghet showed us the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Wailing Wall (from afar) and told story after story of prophets, rulers and holy men and women, how they had seemingly touched and shaped every stone, every broken wall, every corner of the Old City. The story behind every story was that three Abrahamic faiths had lived in conflict and (often uneasy) peace for thousands of years.

“This is the paradise of the Middle East. There is nothing like it anywhere else in the world,” Baghet told me, a statement that etched itself deep in my heart.

We were struck by the silence. We knew Christmas had been canceled in Bethlehem, but we were still taken aback by the utter absence of Christmas in the birthplace of Christianity. It felt like we were the only people, or seemingly the only Muslims, walking through the Old City. As we did, we later realized, a mere 76 kilometers away, at a refugee camp in Gaza, 68 people were killed by an Israeli air strike.

At the entrance to the Al-Aqsa compound, a number of IOF officers milled about. This was the moment of truth for us. Would our teenage son be the deterrent to keep us from entering after we’d come so far? By the grace of our blue passports, we were allowed in.

As is pretty much anyone who visits the Al-Aqsa complex, we were immediately overwhelmed by its religious and cultural history, by its immense importance in Islamic history. At the Dome of the Rock, the Prophet Muhammad ascended to the heavens. It is where, Muslims are taught, Allah gave the Prophet the decree to pray five times daily (after being talked down from 50).

A cat crawls into the lap of Amal Ali as she reads the Quran in the Al-Aqsa Mosque on Dec. 24, 2023. (Photo by Dilshad Ali)

The beauty and tragedy of Al-Aqsa was its silence and serenity. We managed to pray five prayers at either the Dome of the Rock, the Dome of the Chain or within the Al-Aqsa Mosque on our own or in congregation. The congregational prayers we joined (Maghreb and Fajr) contained barely two “safs” (lines) of worshippers, with only scant elderly Palestinian Muslims joined by a few tourist families like ourselves.

A Palestinian American friend, Rana Ottallah, told me, when she heard about our visit, “This is the saddest description of Masjid Al-Aqsa. I am heartbroken (about) how empty it is. You missed the kindness of strangers making you feel at home.

“You missed sitting outside under the olive trees and complete strangers offering you a plate of makloubeh they made for the long trip or a cup of mint tea. You missed seeing the children playing around the gold dome with so much joy and peace.”

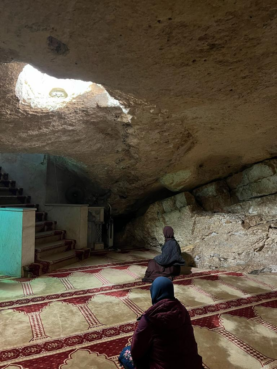

Indeed, when we visited the complex, especially in the early waking hours of Dec. 25 (without a guide, making it feel more risky), it felt like it belonged to us — and to the ever-present cats who patrolled the complex. We knew it should be filled with worshippers. The mood only deepened when we prayed at the Well of Souls (“Bir el-Arweh”), a cave in the Dome of the Rock, its name derived from a myth that the spirits of the dead await Judgment Day there.

An elderly Palestinian cleaning woman asked us where we were from. Upon hearing we were Americans, she joyously hugged us, pressed sweets into our hands and said, “Never stop coming. Go home and tell all your friends and family to keep visiting. We cannot let this place be empty.”

Dilshad and Amal Ali pray at the Well of Souls, in the Dome of the Rock. (Photo by Dilshad Ali)

As the sun rose and lit the gold dome of the Dome of the Rock, we strolled around the complex and found ourselves at the stairs leading down to subterranean large doors that opened into the original halls of the Al-Aqsa Mosque. A caretaker gave us the go-ahead to briefly explore, warning us to leave by 7 a.m., when Orthodox Jews would be escorted in, he said.

We descended into the prayer halls to explore and prayed two “rakat nafl” as a family, a prayer Muslims pray to give thanks or as an act of extra worship.

When we emerged at 7:15 a.m., IOF officers were approaching with a number of Jewish worshippers behind them. Their glances and body language conveyed the message: Time for you to leave.

Leaving the grounds, we realized we may never make it back to this most unique and fragile of holy places, to bear witness to the immense religious and cultural history baked into the very soul of this beautiful place. But we had already overstayed our time, as indicated by those in charge.

(Dilshad D. Ali is a journalist and blog editor for the website Haute Hijab, an e-commerce company that works to serve Muslim women. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)