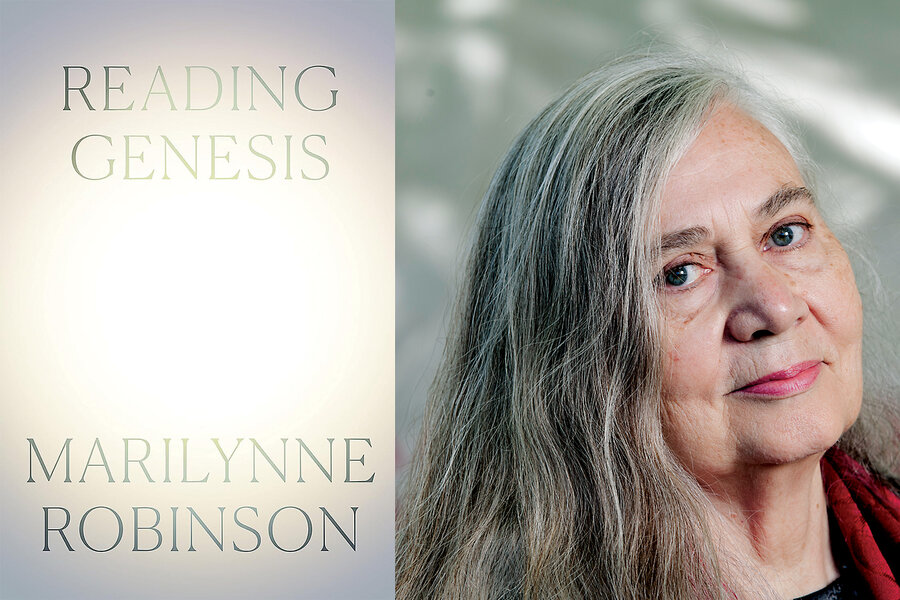

Novelist, essayist, and scholar Marilynne Robinson has managed to thread the theme of goodness into her entire body of work. In her latest book, “Reading Genesis,” she does it once again, unfolding a tapestry of ideas drawn from her keen exploration of the first book of the Bible.

“I imagine a circle of the pious learned rabbis before the word, remembering together what their grandmothers had told them,” she begins, revealing her reverence for a storytelling past, but one that will always have more to tell. Robinson, who won a 2005 Pulitzer Prize for the novel “Gilead,” approaches the first chapter of Genesis as literature, complete with narrative arc and flawed characters who are ever worthy of redemption.

The author is a Christian, but she seeks a deeper understanding of goodness that transcends any particular faith tradition. She states early on that “the metaphysical side of religion, the very conception of the sacred, has vanished like the atmosphere of a lifeless planet.”

In mining for signs of a present and all-good God, she moves beyond interpretations that can keep the Bible locked in the distant past. For Robinson, the operatic tales that occupy much of Genesis provide an opportunity to ponder the idea that – in spite of characters behaving badly – a loving God never deserts His flock.

Robinson gives weight to particular words that reveal her expanded take on Genesis. In the story of Noah and the flood, the whole Earth is rescued by one man – specifically one “righteous” man, a word in the Scriptures that Robinson feels is given too little attention by interpreters. “It can save a city. It can save Creation,” she says. Righteousness indicates that life is “not doomed to destruction.”

The author elucidates other tales such as the Tower of Babel. The people who migrated to Babylon attempted to build a tower that would reach to the sky. The Lord destroys the tower, but more is at stake than punishment for human pride and overreach. She reflects on the “flawed cleverness” of the tower builders. In scrambling the Babylonians’ language and disrupting communication, “The Lord reacts not to what people have tried and failed to do, but to what they might do,” she writes. The story lays the ground for “the potential for human success in doing the impossible.”

Her reading of the Tower of Babel account leads to a consideration of motives beyond human achievement – an impulsion toward a higher, spiritual source. Pivoting to the present, she comments that events in recent decades have taken “an especially apocalyptic turn,” suggesting our “overplus of human ability.”

Robinson applies her particular reasoning to other stories, including that of Hagar and Ishmael. Many interpretations of Genesis have “unvalued” the role of Hagar, the Egyptian servant woman who bore Abram a son – Ishmael – when Abram’s wife Sarai was initially unable to conceive. Sarai’s jealousy sets in motion the banishment of Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness, where they nearly perish. Robinson underscores that this bondwoman – an outcast who may seem peripheral to the story – is very much valued by God. The author reasons that “what actually matters is the value the text finds in her, and in her life, which, humble as it may seem to us, can be called her destiny.” This “destiny” gives importance and dignity to Hagar’s story, as God promises Hagar that Ishmael will raise up a great nation of his own. It speaks to a God committed to the lives of “pagans, kings or slaves.”

“Reading Genesis” is not a Bible reference book. Robinson, by not taking the words of Scripture at face value, makes her case for God’s enduring covenant with creation. She honors ordinary lives in the Bible narrative that “might not feel much changed in being made recipients of divine intention, of promises that will work themselves out over millennia.”

The stories in Genesis can be seen as just as vital today as when they were first set down on papyrus. In “Reading Genesis,” the author counters a literal, religionized view of the chapter. Never forceful or pedantic, she leads readers to draw conclusions of their own, as she points to truths beyond the events depicted.

No matter how off course the characters drift, God remains constant, Robinson tells us. This can provide today’s readers with an uplifted sense of themselves and what they are capable of. In the end, she seems to be shining a light on their own redemption. “The Bible itself indicates no anxiety about association with human minds, words, lives and passions,” she writes. “A notable instance of our having a lower opinion of ourselves than the Bible justifies.”