I often feel I was born in the wrong era. Starting in middle school, I became mesmerized by history of the Civil Rights Movement, especially the courage of Black church leaders through the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the passion of student leaders in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Many of these leaders were deeply inspired in their fight for freedom and human dignity by the Bible, from God hearing and answering the cries of the Israelites in Egypt, to the proclamations of the prophets, to Jesus’ radical teachings and witness.

One of the high-water marks of this seminal period of activism was the “Freedom Summer of 1964,” which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year. During that historic summer, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law. That same summer, civil rights organizations mounted a massive campaign to register Black American voters in the state of Mississippi, shining a spotlight on the violent oppression against Black suffrage. We’re also celebrating the 70th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling against public school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education.

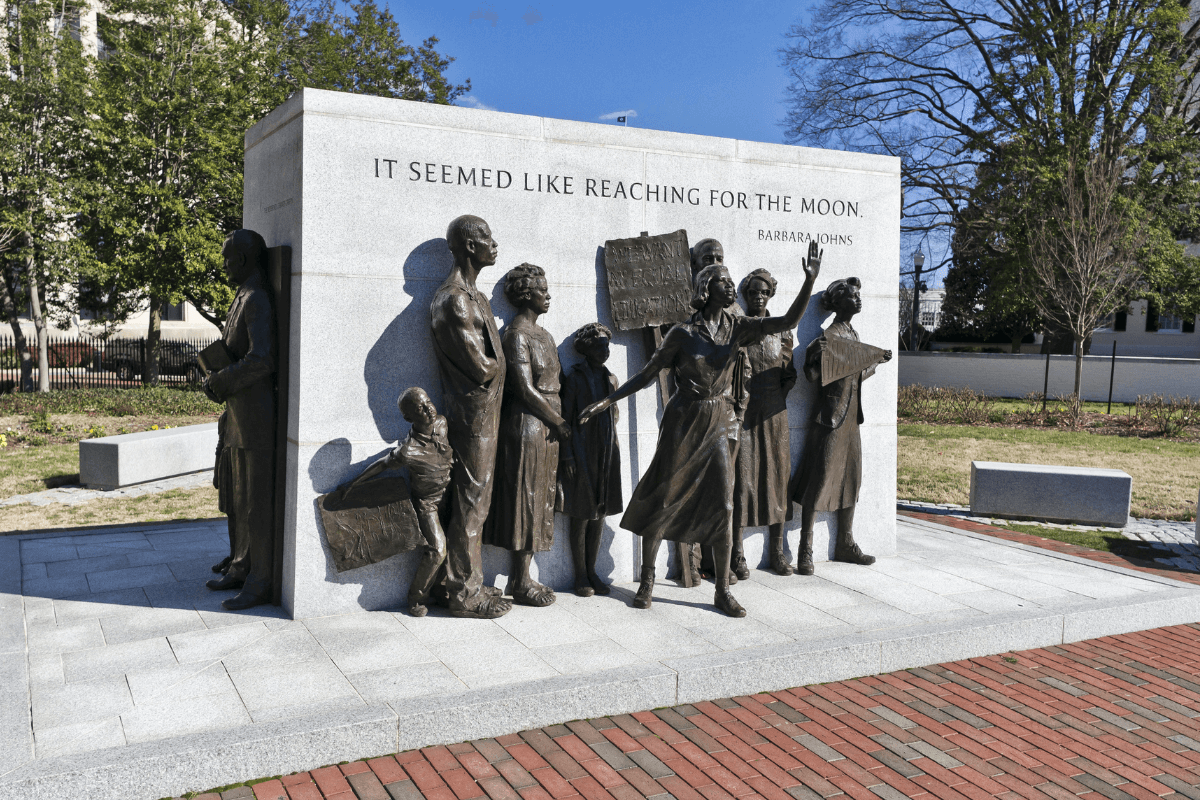

But you don’t have to be a civil rights history nerd to understand why these milestones matter today: In case you haven’t noticed, we’re currently in the midst of a major backlash against racial justice, including many of the rights and freedoms that inspired civil rights leaders. These include book bans, assaults on DEI programs, the Supreme Court’s decision to end affirmative action programs in higher education, and forestalled efforts to transform our justice system and end racialized police violence. These courageous actions taken by our predecessors aren’t just a milestone to celebrate with a nice speech and a historical plaque; these actions reverberate through time, offering us inspiration and resilience for the unfinished cause of freedom and justice.

So rewind to 1954, a year that brought us TV dinners, transistor radios, the term “rock ‘n’ roll,” and the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance. That summer, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. When the ruling was issued, southern states quickly declared their intention to defy it through organized “massive resistance” that engaged multiple tactics to forestall school integration, in some cases for decades. Many white Christians joined these efforts, and some private Christian schools were started as what historians call “segregation academies,” or schools intended to remove white children from integrated public schools.

Today, we know all too well that the fight for equitable education for Black Americans remains what NAACP President and CEO Derrick Johnson described recently as “an uphill battle.” Two recent examples of this battle include the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision to effectively end affirmative action and ongoing efforts to erase Black history in schools. I’ve written about both of these developments with considerable alarm as they’re part of a predictable backlash that followed greater awareness and support for racial justice in 2020.

While overt racial segregation remains illegal as a matter of law, the reality of systemic racism means that inequities — from wealth to employment to housing to the criminal justice system —are woven throughout our society, resulting in de facto segregation in many communities. Recent research from Stanford and the University of Southern California shows that racial segregation has increased 64 percent since 1988 in the country’s 100 largest school districts.

I don’t raise these ongoing challenges to minimize the momentous impact of Brown v. Board of Education; the ruling revoked the odious logic of “separate but equal” of Jim Crow laws, thus catalyzing the mid-century Civil Right Movement over the decade that followed. But for those of us dealing with the current backlash against racial justice today, we need to remember that after Brown, it took a full decade — and a tireless protest movement — before major federal legislation dismantled most of Jim Crow.

I’m speaking of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law 60 years ago this July to forbid discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. The Civil Rights Act had major impacts on access to voter registration, federal programs, public accommodations, and employment, and laid the groundwork for legislation that followed like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Though the 1964 Civil Rights Act was a major legal setback for white supremacy, when we look around today, we see that ideologies of racial exclusion found ways to adapt: Because the narrative of racial inferiority — and thus opposition — to racial equity remained embedded throughout much of U.S. society, these inequities persisted and evolved through discriminatory redlining policies in housing and the exodus of many white students to the suburbs and private schools, leaving many urban public schools under-resourced and increasingly segregated. Bipartisan support for voting rights has eroded over the past 20 years particularly after the Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby County v. Holder case that significantly weakened the Voting Rights Act by removing key provisions. Since this decision, we have seen a barrage of new voting barriers and restrictions that are often designed to suppress voting by Black and brown communities. From our vantage point in 2024, the enduring evolution of white supremacy should push us to consider what efforts are still needed today to challenge these ideologies — and the potential resistance we might face. We must also take seriously the ways in which our Christian faith has been weaponized to justify so much of this resistance, including through the alarming resurgence of white Christian nationalism.

Which brings us to the “Freedom Summer”: Sixty years ago, in the summer of 1964, a multiracial team of volunteers from across the country went to Mississippi to directly challenge the apparatus of Jim Crow that was still very much intact, court decisions like Brown notwithstanding. Over the course of that summer, volunteers and Black residents registered voters and empowered Black students through “Freedom Schools” that taught Black history and civic and economic empowerment. The resistance from local residents was intense and in many cases violent: Eighty of the volunteers were beaten, 37 churches were bombed or burned, and at least seven people were murdered. The violence meted out on Freedom Summer volunteers and Black Mississippi residents alike increased political pressure on Congress and President Johnson, galvanizing political pressure behind the later passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Given the backlash to Black history and empowerment today — let alone to efforts to seek repair through reparations — we need to reclaim the spirit and vision behind the Freedom Summer. Fortunately, many organizations are answering this call, including the 30-year work of the Freedom Schools movement led by the Children’s Defense Fund; events and actions organized by the Freedom to Learn coalition (of which Sojourners is a member); and the National Council of Churches’ Freedom Summer, which will be registering voters and educating and empowering people for social change, especially in advance of the 2024 election.

When I think about all three of these watershed moments — Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act, and the Freedom Summer — I’m struck by the deep role that faith played. Alongside people of conscience and other faith traditions, many of those within the Civil Rights Movement committed themselves to many years of action precisely because of how they understood their Christian faith.

When Jesus preached his first major sermon in Luke 4:16-19, he read the passage from Isaiah 61 that proclaims, “The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” It’s a proclamation that explains the fundamentally liberatory character of God and God’s promises. Through this proclamation, we can see our own nation’s struggle to uphold equal rights for all as achieving the liberation that God so clearly wants for all God’s people. This is what our forebears saw in the Civil Rights Movement: By seeking equal justice for the descendants of those who had been brought here as chattel slaves, we bring this world closer, bit by bit, to the kingdom of God.

How do we then understand the setbacks that we’ve also seen in the intervening decades, from the backsliding to the painfully unfinished work of achieving an equitable and just multiracial society? The answer is both simpler and less satisfying than we might wish: the work of bringing about God’s kingdom “on earth as its in heaven” is not a straight line, and it won’t be finished until the day Jesus returns. But as Paul so memorably instructed the Galatians, “Let us not become weary in doing good, for at the proper time we will reap a harvest if we do not give up” (6:9). These watershed anniversaries are inspirational reminders that never growing weary of doing good and pushing tirelessly for justice can in fact move mountains and change history. Now it is our turn to keep pushing.