Aye Habila, a veteran mentor for the Stand With a Girl Education Project (SWAGEP), is leading what the initiative calls a “safe space” session for a group of 14- and 15-year-old girls who live in the Wassa camp for people who are displaced. A good-natured argument breaks out over the meaning of “negotiation.”

“The girls want a relatable definition,” Rose Geoffrey, Ms. Habila’s assistant, tells her. Ms. Habila then compares “negotiation” to haggling in the market – a familiar scenario for many of the girls, as their parents often send them out to hawk goods. Some girls request a translation from Ms. Habila in Hausa, their native language. One asks for the English definition to be repeated, and then lurches toward her bag for a book and pen to write it down.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Many Nigerian girls displaced by insurgency don’t attend school. “Safe space” educational sessions are giving them access to education again.

The biweekly sessions are a key component of SWAGEP, which enrolls out-of-school girls who live in the Wassa camp and gets them ready for formal education.

“The safe-space curriculum is girl-centered, emphasizing life skills, numeracy, and literacy,” says Margaret Bolaji, the founder of SWAGEP.

At 2 o’clock on a Friday afternoon, a group of teen girls is gathered in an almost bare, sun-dappled classroom on the outskirts of Abuja, Nigeria’s capital. The walls are lined with handwritten cardboard posters. One of them displays a sequence of numbers in descending order, another lists two-letter English words, and beside those is a chart titled “Options for Making Money.”

Aye Habila, a veteran mentor for the Stand With a Girl Education Project (SWAGEP), is leading what the initiative calls a “safe space” session for this group of 14- and 15-year-olds who live in the Wassa camp for people who are displaced. Soon, a good-natured argument breaks out over the meaning of “negotiation.”

“The girls want a relatable definition,” Rose Geoffrey, Ms. Habila’s assistant, tells her. Ms. Habila then compares “negotiation” to haggling in the market – a familiar scenario for many of the girls, as their parents often send them out to hawk goods. Some girls request a translation from Ms. Habila in Hausa, their native language. One asks for the English definition to be repeated, and then lurches toward her bag for a book and pen to write it down.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Many Nigerian girls displaced by insurgency don’t attend school. “Safe space” educational sessions are giving them access to education again.

The biweekly sessions are a key component of SWAGEP, which enrolls out-of-school girls who live in the Wassa camp and gets them ready for formal education. The sessions are held in venues arranged by the camp leaders, and cater to four groups of adolescent girls and young women ages 10 to 20.

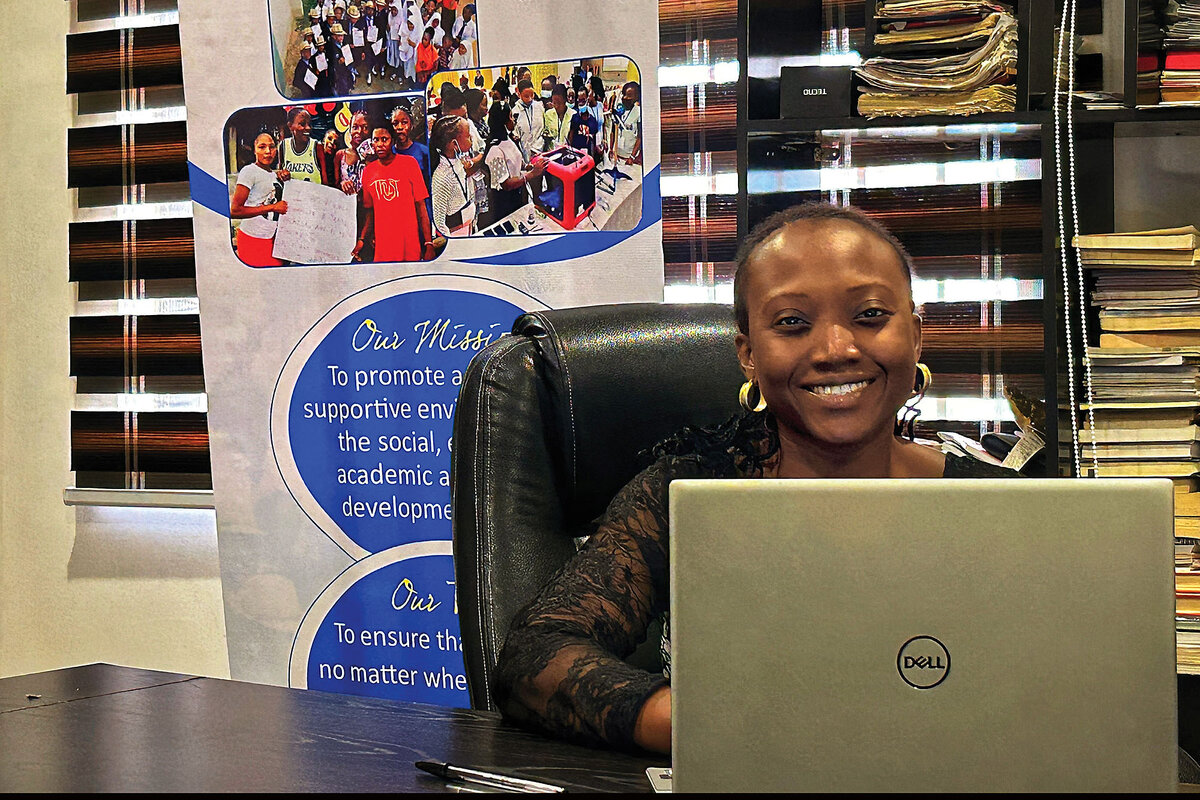

“The safe-space curriculum is girl-centered, emphasizing life skills, numeracy, and literacy,” says Margaret Bolaji, the founder of SWAGEP.

Forced out by insurgency

In 2014, the same year that the abduction of nearly 300 girls from a school in Chibok in northern Nigeria grabbed international headlines, Mary Musa and her family were displaced from their community in Borno state by the Boko Haram militant group. Many families in the Wassa camp share similar stories.

After settling in the camp, Ms. Musa’s parents managed to enroll her in school. But their meager income covered her education only through the junior secondary level. She then spent three years at home until SWAGEP intervened. Now 18 years old, Ms. Musa is approaching her final year of secondary education.

Globally, 250 million children are out of school, with 1 in every 5 of these children living in Nigeria, according to UNICEF. Girls have a higher out-of-school rate in Nigeria, particularly the northern region.

“In addition to insurgency, cultural norms, negative bias towards female empowerment, and poverty contribute to the northern region’s low female education rate,” says Faith Adamu, the Nigeria-based education officer at the Norwegian Refugee Council, an independent humanitarian organization that helps people who have been displaced. Ms. Adamu previously spent nine years at the Center for Girls Education, an organization based in northern Nigeria, developing projects to support adolescent girls. Ms. Bolaji had sought help from the center while developing the safe-space curriculum for SWAGEP.

Before launching SWAGEP in 2021, Ms. Bolaji carried out a survey and found that about 600 girls in the Wassa camp were out of school. “The sad reality is that most of them are likely going to be married off before they turn 18,” she says.

Despite similar conditions in other camps, Ms. Bolaji chose to focus on Wassa. “They gave us the warmest welcome,” she says.

The first group of girls enrolled in schools was supported with money from Ms. Bolaji’s savings and funds raised from her friends and family members. SWAGEP also “organized online campaigns asking people to support a girl’s tuition fees, even if only for a single school term,” she says.

“She goes the extra mile”

After 12-year-old Hassana Ahmadu completed fourth grade, her parents told her that they could no longer afford to sponsor both her education and her brothers’. “They asked me to drop out since I was female,” she says.

After two years at home, Hassana, who wants to be a nurse, learned about the safe-space sessions from the previous cohort and applied. Her mentor, Christine Ibezim, has been impressed by her progress. “She goes the extra mile to communicate in English,” Ms. Ibezim says.

Last year, SWAGEP received significant funding from EMpower, an international, youth-focused foundation. This coincided with the establishment of the safe-space program, which has activities similar to a traditional classroom’s. But Ms. Bolaji is quick to point out that they are not the same.

“The facilitators here are called mentors, not teachers,” she says. She explains that the girls are also exposed to vocational skills. In June, the girls went on an excursion to a shopping complex in Abuja – a rare experience for most of them. “It was an eye-opener for the girls,” Ms. Bolaji says.

Ms. Adamu adds, “The safe space covers topics outside the scope of formal education.” The life-skills curriculum includes areas such as communication, self-esteem, and self-care. Within the past year, Ms. Adamu worked with Ms. Bolaji to replicate the program in a camp in Borno.

The safe-space sessions run for six months, concluding in August, just before a new school year starts. So far, 75 girls total from the Wassa camp have been registered, with 10 graduating from the program and seven of those currently enrolled in school.

Ms. Bolaji aims to help 1,000 girls return to school. “We are not on track,” she says, rubbing her thumb against her other fingertips. “We didn’t anticipate the high costs,” including for transportation and random fees charged by schools, she explains.

Ms. Bolaji says she believes the situation would improve if the government established a school in the camp, in line with national policy recommendations. In 2021, the government introduced a pilot education program in the camp, but it did not offer classes beyond third grade.

Nongovernmental organizations “can’t do everything; they exist to complement government efforts,” Ms. Adamu says. After the first year of the coronavirus pandemic, “Donors cut down on funding, hence the need for a systems approach involving parents, [the] community, and policymakers,” she explains.

Ms. Bolaji notes that she has had more success getting support from the Wassa community than from the government. Among the program’s volunteers is the camp’s chair, M. Bitrus Geoffrey, who was won over by SWAGEP’s consistency. “Some organizations come once, and you never see them again,” he says.

Back in the classroom, Ms. Habila asks the girls to name places where they feel safe.

“The mosque,” a girl blurts out.

“Church,” another chimes in.

A third girl says softly, “Here.”

“The safe space has been magical,” says Ms. Bolaji, her eyes lighting up. “And the girls? They’re our best teachers.”