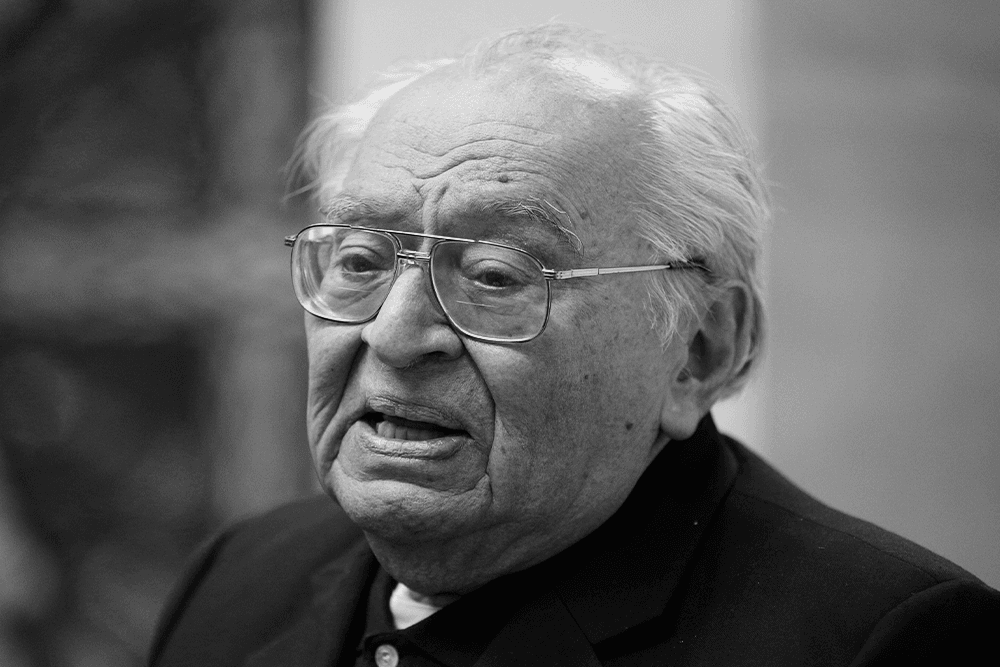

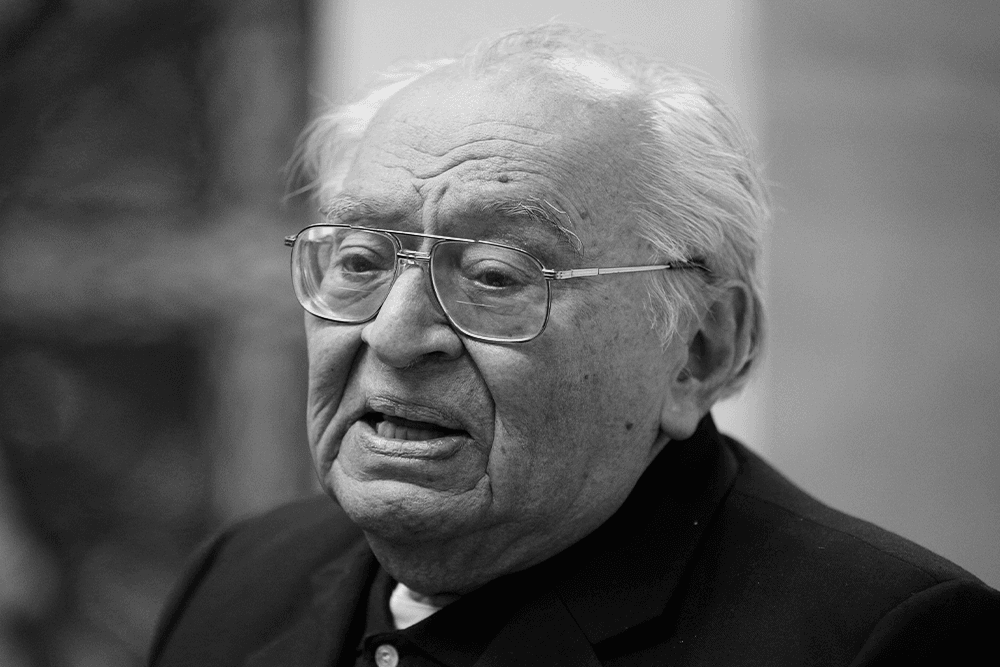

“To do theology is to write a love letter to the God I believe in, to the people I live among, and to the church to which I belong.” —Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, translated by the author

It was an ice-crack freezing January day in the mountains of the Eastern Sierra Madre in northern Mexico. I was moderating a table at a gathering to mark the 25-year-episcopacy of the outspoken bishop, Don Raul Vera, my co-president of the historic Óscar Romero International Christian Network in Solidarity with the Peoples of Latin America. To my right and to my left sat the titans of liberation theology: Father Jon Sobrino, SJ, a survivor of the massacre at the Central American University in San Salvador; Father Eleazar Lopez Hernandez, founder of the Teologia India movement; and farthest away, the grandfather himself, Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, from Lima, Peru, and a Dominican, like our honored Don Raul. It was so cold — no heat at all in the center — that someone had gone around and collected wool blankets.

I was shaking in my boots for other reasons. What on earth was I, a Canadian, Anglican, female priest doing at this table? What possibly could I contribute to this conversation? But that was the point. Liberation theology was the work of many. Gutiérrez had systematized a living, collaborative, community movement in his ground-breaking work, A Theology of Liberation, published in 1971 in Spanish and two years later in English. Over decades, clerics and community leaders, men and women, across cultures, identities, and denominations, all had contributed, in the smallest way, to the construction of this new way of thinking about — and acting toward — God and God’s glorious creation.

A Theology of Liberation was what made it possible for me to be a Christian in the first place. Though my grandmother was a Catholic Worker, I grew up in a profoundly secular household with a strong sense of the injustices of the world. I had married into the struggle in Guatemala, where I lived and fought for years amid horrendous oppression and fierce violence. It was a surprise, and an utter joy for me to discover that God, and God’s people, were active and involved in challenging unjust systems and coming alongside those most vulnerable. But how had this come to be, I wondered.

Evolving out of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) and the 1968 Medellin Conference of Bishops, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Latin America tipped off a wave of change that would leave no corner of the continent untouched. In my heartland of Guatemala, priests and nuns, religious brothers and bishops, left their hallowed halls and went into the countryside. Agricultural and banking co-ops were formed, study groups sparked to life, lay people (mostly men) by the tens of thousands were empowered to take leadership in their communities. This renewal movement spread across Latin America, a powerful example of people rising up.

What happened next was unspeakable: oppression up and down the continent, a dirty war in Argentina, coups in Chile, Brazil, Haiti and elsewhere, genocide in Guatemala. Christians — particularly those practicing liberation theology — were not immune to these waves of violence; they were often its target. Thirteen priests were killed in Guatemala. Bishops Óscar Romero, Enrique Angelelli, and Juan José Gerardi were murdered in El Salvador, Argentina, and Guatemala, respectively. Thousands upon thousands of lay people were martyred.

Sadly, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church during much of this time did little to defend its members practicing liberation theology. Pope John Paul II, whose roots were in a Poland suffering under communism, would do little to uphold the innovative model of church initiated by Gutiérrez and his like-minded keepers of the faith.

This is what I was thinking on that frigid January afternoon. The liberation church at that time was struggling under an even more rigid pontiff, Pope Benedict XVI. The core of what I said to these gathered men and women was, “Hang on. Our love for the poor will sustain us.”

As we left the conference table together, Gutiérrez took my hand and shook it warmly. He said nothing but nodded at me with affection. We became friends, colleagues, allies. I noticed then that he walked with a pronounced limp. He had suffered polio as a young boy and lived his life with ever greater restrictions on his movements. But he was unstoppable.

Little did we know, on that cold day in 2013, that in three months the whole church would begin to turn over with the election of the first Latin American pope, Francis. While Francis wasn’t exactly a liberation practioner, he was more open to a change. Within a year, Gutiérrez was in Rome, in conversation with the new pontiff.

Gutiérrez, who died on Oct. 22 at the age of 96, never stopped practicing as a parish priest. In 1974 he founded the Bartolome de las Casas Institute in Lima. In its 50 years of work, it has celebrated and lifted up community struggles, from defense of the Amazon, to leadership schools, to popular theology studies. Gutiérrez also took his theology into the educational institutions of the church and for decades taught theology at the Pontifical University of Peru and the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. For rich and for poor, for privileged and oppressed, Gutierrez knew the road to right living was through sharing the joyous creation of God’s riches.

The first notice I had of our brother’s death was on the SICSAL leaders’ WhatsApp chat. The note was from Ana Ruth Garcia, a feminist theologian and Baptist minister from Honduras who serves as a tireless defender of the LGBTQ+ community and women’s reproductive rights in a place where a miscarriage could land a woman in jail if it was suspected she had had an abortion. Her text read, “Our Grandfather has gone ahead of us.”

When I saw her message, my heart was not grieved but warmed. We are all family, all one, with this Lord of Life.

This prayer from SICSAL Ecuador member Nidia Arrobo Rodas was shared around the world with joy; here is my English translation:

“Gustavo, your interpretation of Exodus ignited the spark in our Latin American Church … a continent torn by the contradiction between Christian faith and scandalous social inequality… San Gustavo, continue to guide our Christian walk with your magnificent work so that we may fully live our commitment to the marginalized … from the heart of God, accompany the suffering people who need a light of hope.”