Soon after sunset one evening in August, a few days after the late-summer full moon, the coral species Acropora cervicornis decides it is time to breed.

During an approximately 140-minute window, this coral – commonly known as staghorn in a reference to its branchy, antler-shaped structure – releases a snow globe display of gametes into the water: packages of egg and sperm that ride the ocean’s currents toward nearby but genetically distinct reefs. There, they will meet other staghorn gametes that have also spawned, coordinating somehow across a watery expanse with guidance from the moon, the currents, and each other.

In a best-case scenario for the coral, these mixing gametes will fertilize, exchanging the sort of genetics that allow for resilience in what has always been a changing ocean world. They will develop in the water for a number of days, then the larvae will sink and settle on clear patches of reef substrate – the real estate available for coral babies – where they will grow and live for the rest of their lives, forming a key part of the ecosystem that protects and supports coastal communities worldwide.

Why We Wrote This

Scientists, in a shift from the tradition of not meddling in nature, are replicating coral that shows surprising pockets of resilience amid warming oceans.

But for coral these days, it is far from a best-case scenario.

Over the past decades, humans have disrupted this finely tuned dance of coral procreation. Because of damage from both climate change-charged storms and climate change-accelerated die-offs, reefs are often so far apart that wandering gametes simply never float into mates. The substrate is also more likely to be covered with seaweed thanks to changing water temperatures and pollutants, which leaves fewer places for coral to settle. And those baby corals that do find homes are increasingly stressed by warming ocean waters.

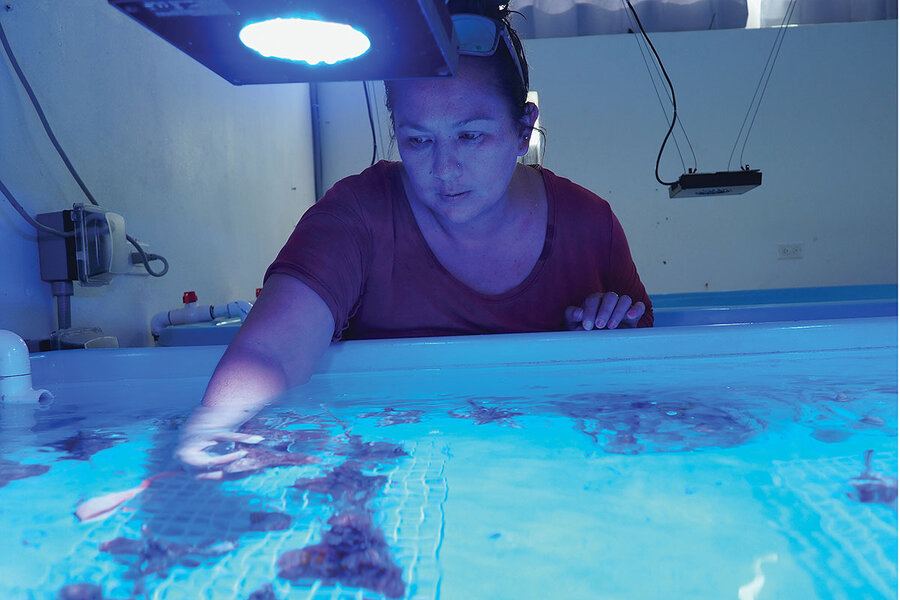

Which is why Natalia Hurtado, lead scientist with the Bahamas Coral Innovation Hub on the southern side of the island of Eleuthera, is trying to give the coral a bit of help.

Ms. Hurtado, who grew up in Colombia and has worked on coral research around the world, is part of a loosely connected international army of scientists, conservationists, and policymakers who are trying to boost coral’s resilience. She and others on her team – a collaboration between the Bahamas-based Perry Institute for Marine Science and the Cape Eleuthera Institute, as well as The Nature Conservancy – are working to record and predict the dates and times of coral spawning, from the once-a-year event of the staghorn to the monthly efforts of the grooved brain coral.

From this research, they have made a chart that helps other scientists and divers do what’s called larval propagation. That basically means taking an evening dive, scooping up floating gametes, fertilizing them in a laboratory, giving them a good place to live, and eventually returning them to the reefs.

Ms. Hurtado has also been evaluating the resilience of different corals growing from this sort of human-assisted mating, and from coral transplants that have come from nearby reefs. She maintains an underwater nursery a short boat ride away from the Cape Eleuthera Institute, which has some 22 “trees,” usually plastic structures covered with coral anchored to the ocean floor, as well as a land-based nursery of different experiment tanks.

At both locations, her team records how the different coral genomes are faring, with an eye toward finding those most likely to survive rising ocean temperatures.

“The ones we have are resilient,” says Ms. Hurtado. “But some do better than others.”

The goal, she and other scientists say, is to plant these particularly resilient specimens back onto the reefs. And that, they hope, will give the ecosystem a better chance to survive in a world changed by human-caused warming.

Not long ago, this type of human-assisted evolution and rehabilitation would have been on the fringe of environmental work – the target of skepticism and critiques about heavy-handed intervention in natural systems. But in recent years, more conservationists have embraced this sort of human-animal partnership when it comes to adapting to climate change. It is a shift in the basic understanding of resilience – and not just for coral, but for climate-threatened species around the world. And while it may test the bounds of scientists’ and conservationists’ understanding of “natural,” it is also offering new connection and hope.

“There are these natural adaptive capacities that are unique to this system that we can start to exploit,” says John Parkinson, a coral researcher and assistant professor in the department of integrative biology at the University of South Florida in Tampa. “That might be also true in other systems. It’s a concept of working with evolution, not against it.

If coral is an example of a species that could be helped by genetic assistance, it is also unique.

Coral reefs, explains Elizabeth McLeod, who leads global reef work for The Nature Conservancy, are some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth. Although they take up less than 1% of the ocean, they support about 25% of all marine life. Reef fisheries support the livelihoods of a half-billion people worldwide, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the ecosystems are hugely important for tourism. White-sand beaches are connected to coral.

Reefs also provide coastal protection by buffering shorelines against storm surges, floods, and erosion – dissipating as much as 97% of incident wave energy, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. This, scientists say, is increasingly important as climate change and warming ocean waters increase the severity of hurricanes.

But coral reefs are at risk. According to the United Nations, the world is poised to lose as much as 90% of its remaining coral reefs by 2050 if actions are not taken to reduce threats. Already, some scientific reports estimate that oceans have lost half of the reefs that existed in 1950.

“There’s a huge knockdown effect if we lose coral reefs,” says Dr. McLeod. “That’s something to keep in mind when we talk about the potential to lose 90% of reefs. What that means is we’re losing the coastal protection that they provide; we’re losing fisheries habitat that they provide; we’re losing the tourism dollars that they provide. So their loss would have really significant impact.”

This worry is far from new, though. For decades, environmentalists have been warning about reef degradation. In the 1980s, nonprofit and academic organizations began joining forces to protect reef ecosystems after researchers discovered widespread coral bleaching – a phenomenon where coral expels the colorful symbiotic algae that live inside it. This happens when coral is particularly stressed, usually because of high water temperatures or pollution.

“The range coral can live in is narrow – the ideal is 82 degrees Fahrenheit, 28 degrees Celsius. There they do very well,” says Valeria Pizarro, head of the coral reef team at the Perry Institute. “If the temperature rises to 32 or 33 degrees in Celsius, the coral gets pale, or bleaches. … That means they are dying.”

In 2000, the United States signed the Coral Reef Conservation Act to establish the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. By 2003, the U.N. Environment Program’s Coral Reef Unit decided it should put together a document that outlined the growing number of worldwide conventions, treaties, and initiatives that had been formed to help coral reefs. It was intended to help scientists and the international community better coordinate this conservation work.

At the time, most of these efforts were focused on protection and preservation. That fit an early 2000s conservation ethos that often prioritized regulating human activity and setting aside “protected areas” to help sensitive ecosystems. Very few scientists at the time were trying to grow coral themselves. And those who were doing it were often seen as outliers, even dangerous.

Part of that, explains Dr. Parkinson, is that for decades, conventional scientific wisdom was that humans simply shouldn’t meddle in nature. Growing coral for different attributes and replanting it on reefs could lead to unintended consequences; the logical outcome of these endeavors was a changed reef ecosystem.

But over the past decade, the effect of climate change on the oceans has become ever more apparent. Although much discussion about global warming focuses on air temperature, it is the oceans that absorb most of the heat generated by rising emissions – around 90%, according to the U.N. This has led to glacier melting in polar regions and sea level rise. It has also led to marine heat waves. In 2021, nearly 60% of the world’s ocean surface experienced at least one spell of marine heat waves, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. And this, scientists say, has caused even more rapid coral loss. A 2021 study conducted by the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network estimated that 14% of the world’s coral disappeared between 2009 and 2018.

But even as researchers panicked at the rapid loss of coral, they were beginning to notice something else: There were glimmers of unexpected resilience within this seascape of devastation. Some reefs, they realized, seemed to be doing just fine, despite the changing conditions. Others that had bleached and seemed to be in a death spiral actually recovered. And some individual corals in one place were faring far better than the same species nearby.

One scientist who decided to zoom in on this phenomenon was the late Ruth Gates. She directed the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and she wanted to understand these pockets of resilience. She believed that if humans could find and replicate the genetics behind these success stories, then reefs overall would be more likely to survive.

“Not all corals are created equal,” Dr. Gates said later in a university publication. “We will capitalize on those corals that already show a stronger ability to withstand the changing ocean environment and their capacity to pass this resilience along to new generations.”

She established a lab for what she called the human-assisted evolution of coral, and in 2013, the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation awarded Dr. Gates and a collaborator from the Australian Institute of Marine Science its $10,000 Ocean Challenge grand prize. Two years later the foundation agreed to provide an additional $4 million grant to support their work.

“They had this idea at the time to increase the resilience of critical and highly vulnerable coral reef ecosystems,” says Lara Littlefield, executive director of partnerships and programs at Vulcan, which advises the Allen family foundation. “This was the type of work that people weren’t really talking about at the time; it was really considered fringe.”

At first, Ms. Littlefield says, mainstream conservationists worried that focusing on genetic resilience would take away from the all-important effort of reducing the pressures on coral in the first place, whether that meant pushing for lower greenhouse gas emissions or stopping overfishing. But soon other academics and conservation groups began to follow suit, adopting a “you have to do both” approach.

The same was true for coral nurseries, says Dr. Parkinson. At first, conservationists in Florida, where his underwater nursery is located, looked askance at “coral gardening,” or growing coral on “trees” and other rebar structures. But over the past decade, a vast majority of research institutions have embraced the coral nursery approach.

“It’s a big shift,” says Dr. Parkinson. “We’ve gone from thinking that we shouldn’t be involved – that we should just be marking off territory and saying, ‘This is a reserve and we won’t manipulate it’ – to ‘Active interventions are worth doing.’ Because we know now that if we don’t do anything, the risk is really high that you are going to lose coral. … Restoration is ‘We want to preserve what was there in the past.’ I don’t think anybody thinks we can do that for coral anymore. The climate is changing too fast. The world is changing too fast.”

But the physics of coral resilience isn’t so straightforward – either scientifically or logistically.

From a practical point of view, growing and raising coral – from catching the floating gametes to keeping nursery structures clean – is a massive undertaking. The science behind coral resilience is also immensely complicated, with researchers still decoding the secrets of why some individual corals seem particularly suited to withstand heat, acidification, and other changes connected to climate change.

Scientists, for instance, are still trying to understand the role of the algae that live in coral and whose photosynthesis provides a large percentage of the coral’s food. They know that most coral will expel its algae when the water temperature increases, but they are still investigating how the genetics influence that process – why one coral and algae pair will remain together when a nearby pair won’t. They’re also studying what happens when coral forms a relationship with other, more heat-tolerant species of algae.

Meanwhile, new research suggests bacteria, archaea, and fungi seem to have a substantial, yet previously unknown, impact on the ability of reefs to deal with changing water temperatures and disease, says Anya Brown, an assistant professor of evolution and ecology at the University of California, Davis’ College of Biological Sciences. New studies also suggest that microbiomes connected to other nearby species, such as seaweed, may impact coral vitality, even when not directly adjacent to it.

In other words, there are connections, and resilience, throughout the ocean and reef ecosystems that science can’t yet explain.

“Right now there are different levels of triage happening,” says Dr. Brown. “You have to grow corals and get them out there. Hopefully some will survive. The next question is, how do we optimize this process to maximize our coral survival and growth when they’re in the field or in nurseries? We don’t understand as much as we thought we did about some of these relationships.”

That even includes where reefs exist in the first place. Reef ecosystems, of course, are underwater, so scientists can’t use aerial photography to monitor them the way conservationists study forest canopies.

Steve Schill, the lead scientist for the Caribbean division of The Nature Conservancy, has been trying to get around this by using satellite imagery and sensors, combined with underwater photo mosaics, to map the reefs around the Bahamas and elsewhere in the region. To find “super reefs,” those areas of coral resilience, he and his team have been merging that information with data on storm risk, water temperature, and other factors.

“We want to zoom in on where corals were more likely to survive,” he says.

But coral is tricky, he points out. Just because a reef looks healthy today does not mean that it will be thriving tomorrow. The ocean is always changing. At a certain point, in order to understand and help coral resilience, people must go under the water to take a look themselves.

On a recent day off New Providence Island in the Bahamas, Hayley-Jo Carr, another researcher with the Perry Institute, asks her boat captain to travel to what scientists call the James Bond nursery. It’s named after a nearby shipwreck left over from the 1983 movie “Never Say Never Again.”

The water is glass-clear – enough so that a snorkeler can clearly see a nurse shark gliding by the shipwreck some 40 feet below. But she wants to get a closer look at the PVC trees growing the critically endangered staghorn coral. She also wants to show the nursery to Rose Rijnsaardt, a scuba diving instructor from Aruba whom Ms. Carr had previously trained as a reef rescue diver instructor.

The Reef Rescue Network is a Caribbean-wide effort to bring scuba diving operations, resorts, and other businesses together to help with scientists’ restoration efforts. It’s based on the premise that there simply aren’t enough researchers – and there isn’t enough research money – for scientists to do all of the coral rehabilitation work themselves. If scuba divers, for instance, can be trained to be reef rescue divers, not only can they learn how to do tasks such as cleaning excess algae away from the coral nurseries and keeping an eye out for coral disease, but they can also instruct tourists to do the same. So far, she has trained some 70 reef rescue diver instructors like Ms. Rijnsaardt, who have in turn taught hundreds of other divers to help with reef rescue work.

“We want recreational divers to become involved,” Ms. Carr says. “There’s a lot of underwater work that divers can do.”

Resorts, dive shops, and other businesses, she says, might start finding ways to capitalize on this sort of conservation work. With 31 nurseries throughout the Bahamas, there are a lot of chances for collaboration – and a lot of opportunities for visitors to pay to help further coral resilience.

“We need to make nursery maintenance sustainable,” she says.

Ms. Rijnsaardt nods.

“It is something people will be happy to do,” Ms. Rijnsaardt says.

Ms. Carr jumps off the boat with Ms. Rijnsaardt and Meghyn Fountain, another research assistant. Ms. Fountain, who grew up in the Bahamas capital city of Nassau, has been working to assess the health of different reefs across the country, and spends a lot of time cleaning the nurseries herself.

“You find yourself talking to the coral,” Ms. Fountain says with a laugh.

Ms. Carr gestures below.

“The staghorn grows like crazy here,” she says, referring to the critically endangered coral species that spawns once a year.

They dive down to where the trees are overflowing with coral. Just a short distance to the shore, the Bahamas Reef Environment Educational Foundation has built an underwater sculpture garden connected to the Clifton Heritage National Park, a protected expanse built on the site of a long-abandoned cotton plantation. The largest sculpture, 18 feet tall, is called Ocean Atlas, which depicts a Bahamian girl bent over and seeming to carry the weight of the ocean on her shoulders.

It was intended to be a monument that referenced climate change, and humans’ new role in supporting ecosystems.

The three women emerge from the water.

“They actually look really good,” Ms. Carr says of her coral. Ms. Fountain and Ms. Rijnsaardt nod in agreement. “Really good. I’m happy about that.”