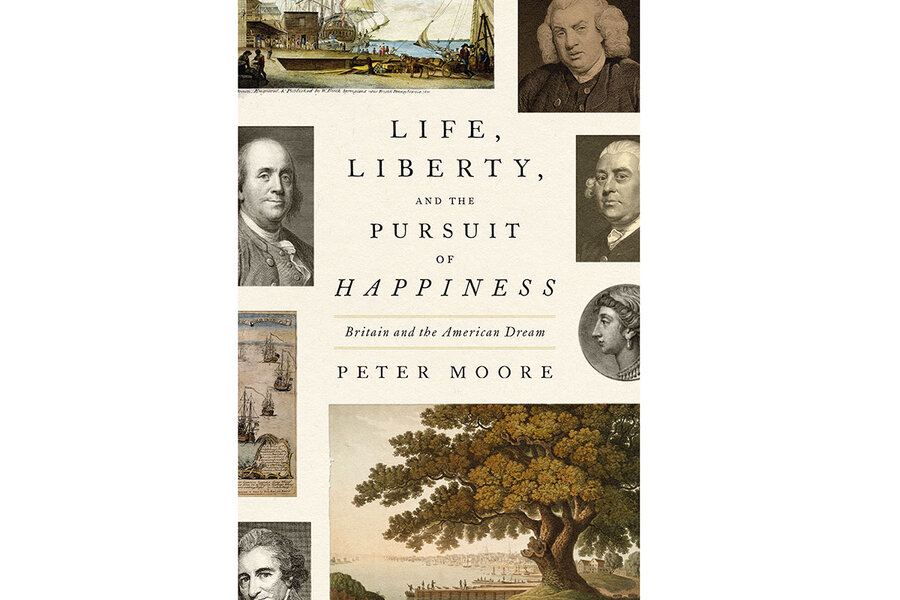

From the time they are schoolchildren, Americans learn what happened after Thomas Jefferson asserted a right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. In his stirring intellectual history, Peter Moore focuses not on the “after,” but on the “before,” tracing the broad shifts in thought, years in the making, that enabled Jefferson and his fellow drafters to conceive of human rights in such a groundbreaking and expansive way.

“Contained in that phrase is so much revealing history,” Moore observes at the outset of his book “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: Britain and the American Dream.” The author chronicles that history in three meaty sections, which elucidate emerging Enlightenment conceptions of each of the three ideals. Broadly, they chart English philosopher John Locke’s notion of life as entailing certain universal rights; an idea of liberty rooted in the safeguarding against tyranny; and a novel view of happiness as a condition to be strived for on earth, not merely in the afterlife.

The action takes place primarily in England and revolves around six figures. Five are British: Samuel Johnson, John Wilkes, Catharine Macaulay, William Strahan, and Thomas Paine. The sixth is Benjamin Franklin – in Moore’s words, “arguably the greatest American that ever lived.” The Founding Father absorbed and engaged with England’s intellectual currents during several lengthy stays in London, where he acted as an agent for the Colonies. Like many in America, he greatly admired the culture and customs of the mother country – to his wife’s dismay, he always found excuses to extend his trips abroad – and only gradually and painfully concluded that the Colonies must separate from England.

In vivid prose, Moore demonstrates why Franklin was so energized by his travels to London. In England, the decades leading up to the American Revolution were, the author writes, “boisterous, expansive, confident, unstable…. Even at the time people knew they were living at a loaded moment in history, when the old ties of parish and church had been loosened, when luxury and corruption had intensified along with the social and economic progress.”

The British thinkers he profiles dramatize this ferment. Johnson, the writer and intellectual best known for his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language, is the most conservative figure featured: He believed it important that, in Moore’s words, “the rage for progress be challenged.” Johnson was decidedly suspicious of Wilkes, the radical journalist and politician whose criticisms of King George III resulted in charges of seditious libel. As Moore recounts, Wilkes portrayed himself “as the champion of English liberty and as a victim of tyrannical ministers.” He was viewed as a hero by many in England and became an inspiration in the Colonies as well.

Macaulay produced an eight-volume history of England between 1763 and 1783. Upon the first volume’s publication, one newspaper marveled that “the History of England by a Lady seems such an extraordinary phenomenon, that every one eagerly asks the reasons of its appearance.” Macaulay believed a free democratic republic to be the most enlightened form of society. “It is only the democratical system, rightly balanced,” she wrote in 1767, “which can secure the virtue, liberty, and happiness of society.” Such views made her a popular figure in the Colonies.

While not as well-known today as the others, Strahan was an important and successful printer; he published Johnson’s work and, later, Edward Gibbon’s “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” and Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations,” which Moore calls “two books that would define the age.” He and Franklin had a long, warm correspondence before finally meeting in London; they quickly became dear friends.

The force of their bond is evident in a letter from Strahan to another friend, in which he wrote of Franklin, “It would much exceed the Bounds of a Letter to tell you in how many Views, and on how many Accounts, I esteem and love him.” The two collaborated on articles attempting to smooth relations between the Colonies and the Crown, but eventually, of course, they found themselves on opposite sides. The pain of that rupture comes alive in an angry letter Franklin wrote, but never sent, to Strahan after the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill: “You and I were long Friends: You are now my Enemy.”

The British-born Paine is a late entrant to the narrative, but Moore charts his quick transformation into a patriotic American after his 1774 emigration to Philadelphia (at the suggestion of Franklin, whom he’d met in London). After civic leader Benjamin Rush had the idea for, in Moore’s words, “a fiery, pulse-raising polemical pamphlet written in pugnacious style by the likes of Wilkes, Macaulay, or Johnson,” he called on Paine to draft what became the explosive pro-independence pamphlet “Common Sense.” In its conclusion, Paine put forth the idea for a declaration laying out the Colonies’ reasons for separation.

That declaration, featuring Jefferson’s indelible phrase, “captured the unique purpose and energy of the American Revolution,” Moore writes. Not everyone was included in its promise, a shortcoming the author alludes to but doesn’t dwell upon. (In 1775, one of the book’s protagonists, Johnson, asked, famously and acidly, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?”) Still, in artfully tracing its history, he has helped explain why “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” has endured as an ideal for nearly 250 years.